There’s a kind of reading that asks for nothing more than your attention. It does not try to pull you forward with suspense or flood your senses with elaborate prose. Instead, it sits with you, quietly, and speaks when you’re ready to hear. For some readers, this kind of writing is rare and precious. It is not about finding out what happens next, but about finding a deeper sense of what is already here.

I have always found joy in this kind of reading. Not in novels that demand constant plot engagement, nor in academic papers that argue their way through dense jungles of logic. But in prose that feels like it was written with care, distilled like spring water, intended not for consumption but for contemplation.

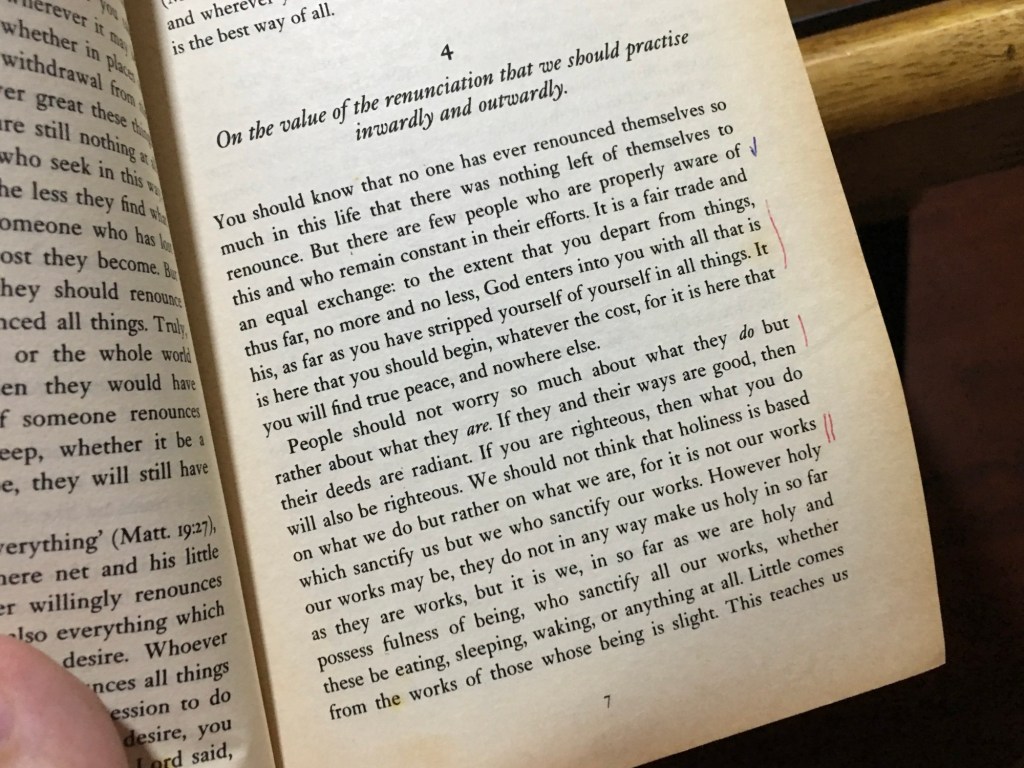

Writers like James Allen or Meister Eckhart gave me this joy. Their sentences carry the weight of thought, but not the heaviness of excess. Each line feels complete, almost quotable on its own. Even their old-fashioned phrases don’t distance the reader; they draw you in. There is sincerity in them. A rhythm. A presence. And most importantly, a quietness that gives space for the reader’s own reflections to enter.

The Problem with Walls of Text

I walked into a bookstore and began flipping through nonfiction books on history and philosophy. Most of them were thick, some intimidatingly so. The covers promised insight and intellectual reward, but the moment I turned a few pages, I was met with long, dense paragraphs that stretched without pause. They formed what I can only describe as a wall of text. Not just physically, but emotionally. They felt impenetrable.

It wasn’t that the topics weren’t interesting; they were. But the structure, the pace, the sheer volume of explanation in each breathless paragraph dulled the senses. It was hard to see where one thought ended and another began. Even the page layout seemed to resist the reader’s entry.

This style, I came to understand, is not accidental. It is inherited from academic traditions, from printing economies, from assumptions about what makes writing “serious.” And for a time, it worked. Long, complex paragraphs were a way to display depth, to show mastery over a subject. But times have changed. Readers have changed. And perhaps most importantly, the way we process meaning has shifted.

Taste, Not Just Text

Reading can be more than decoding information. It can be a form of tasting. A moment of sensory and intellectual presence, like sipping tea or listening to a piece of music in solitude. The act of reading reflective prose, when done well, offers this kind of experience. It’s not about speed or data, but atmosphere. You don’t read to “get through” it. You read to linger.

This is the reason I’ve always been drawn to prose that moves slowly but clearly. Writings that don’t rush to make a point, but allow it to arise gently. It is not a lack of substance. On the contrary, it takes more effort to be simple than to be complicated. But once it’s there, the simplicity allows the reader to receive the thought fully, without noise or strain.

Writers like James Allen, and some from the contemplative tradition, understand that form is not separate from content. The shape of a sentence, the pacing of paragraphs, the presence or absence of silence; these are not stylistic afterthoughts. They are the very vessels in which meaning travels.

A Quiet Lineage

In this pursuit, I’ve noticed a quiet lineage of writers who create this kind of experience. They come from different times and traditions, some monastic, some mystical, some philosophical, but they share a tone. They do not shout or dazzle. They speak gently, yet with weight.

James Allen is one of them. His writing reads like distilled truth. Each sentence offers a meditation, not just a message. And others walked a similar path. Thomas Merton, writing from within the silence of a monastery, offered reflections that were as grounded as they were transcendent. Meister Eckhart, centuries earlier, spoke of the soul’s unfolding with a clarity that feels eternal, not historical.

These are not writers for everyone. But for those who crave a different kind of engagement, one rooted in slowness, in thoughtfulness, in stillness, they are essential companions. Their work doesn’t simply pass on knowledge. It invites the reader into the still interior of things, where truth is not shouted but revealed slowly, in quietness.

Between Information and Imagination

One thing that separates this style from most nonfiction or fiction is that it doesn’t fully belong to either category. It sits between them. It doesn’t just present facts. And it doesn’t just invent stories. It invites the reader into a shared space of reflection.

This is why I’ve come to describe it as “Reflective Clarity.” It’s not clarity for its own sake, like a manual or a guide. Nor is it vague inspiration. It’s the kind of clarity that arises after long thought, then gets offered to the reader without pride or pressure. It doesn’t try to change the reader’s mind. It tries to hold space for the reader’s inner life to rise and respond.

That’s what makes it feel so different from other kinds of writing. It’s less about transmission and more about communion. Less about persuasion and more about presence.

Writing Journey

Looking back, I realize that much of my effort has been shaped by this desire. Even the way I outline my essays, the section titles, the short paragraphs, the natural flow without bullets or summary phrases, is not just a preference. It’s a posture. A way of treating the reader with trust.

I want each sentence to have its own gravity. I want each section to feel like a room you can enter and stay in for a while. And above all, I want the act of reading to feel like an experience worth having, not just a step toward information, but a kind of conversation between two minds across time.

Writers like Dostoevsky and Kierkegaard influenced me deeply. Their themes, their struggles, their existential insights helped shape the way I think. But stylistically, I could never quite follow them. Their writing is often intense, chaotic, layered with multiple voices, full of psychological weather. Powerful, yes. But not a model for my own voice.

James Allen, on the other hand, feels closer to home. Even when I don’t agree with every conclusion, I respect the way he walks the reader through his thoughts, not with force, but with clarity and rhythm. His writing is not a maze. It’s a garden path.

A Style That Listens

If I had to summarize what I aim for in my effort, it would be this: I want the prose to listen. Not literally, of course. But I want it to feel like it leaves space for the reader’s presence. That it doesn’t speak over them or at them. That it gives them time. A sense of breath.

I want to avoid overly clever constructions or self-congratulatory turns of phrase. I don’t want to impress. I want to meet the reader where they are, and then walk with them a little further.

There is a kind of humility in this approach, I believe. It’s not flashy. It’s not quick. But it’s sincere. And in a world that moves fast and speaks loud, that sincerity may be more valuable than ever.

A Reader’s Space

One of the most beautiful things about writing in this style is that it trusts the reader’s intelligence and intuition. It doesn’t explain everything. It doesn’t fill in every silence. It believes that the reader brings their own insight, their own story, their own mystery.

This is why the best reflective prose never feels like it’s preaching. It’s sharing. It’s offering. It’s lighting a candle and placing it on a windowsill.

When a reader finds this kind of writing, they recognize it not by the content alone, but by the way it feels. It feels like being seen. Like being accompanied. And when that happens, the writing becomes more than text. It becomes presence.

The Shape of the Future

I carry with me this quiet ambition: not to become a loud voice in a noisy world, but to remain faithful to the kind of effort that nourishes.

I believe that Reflective Clarity has a place in our time. Perhaps not on the bestseller lists, but in the quiet corners of people’s lives, on bedside tables, in early morning reading sessions, in quiet cafes where someone wants to read something that matters, not just something that moves.

I will continue listening for the right rhythm, the right silence, the right simplicity. And I will continue my effort not to finish a point, but to leave a space where meaning can arrive on its own.

It’s not about the words themselves. It’s about what they allow us readers to feel, think, and become.

Image: A photo captured by the author.