In today’s fast-paced world, where copy-and-paste happens in the blink of an eye, the act of manually copying texts feels like something out of the past. Who has time for that? But what if this old-fashioned practice holds something we’ve been missing? Across cultures and centuries, people have copied texts by hand—not just to preserve knowledge, but as a way to connect with it on a deeper level.

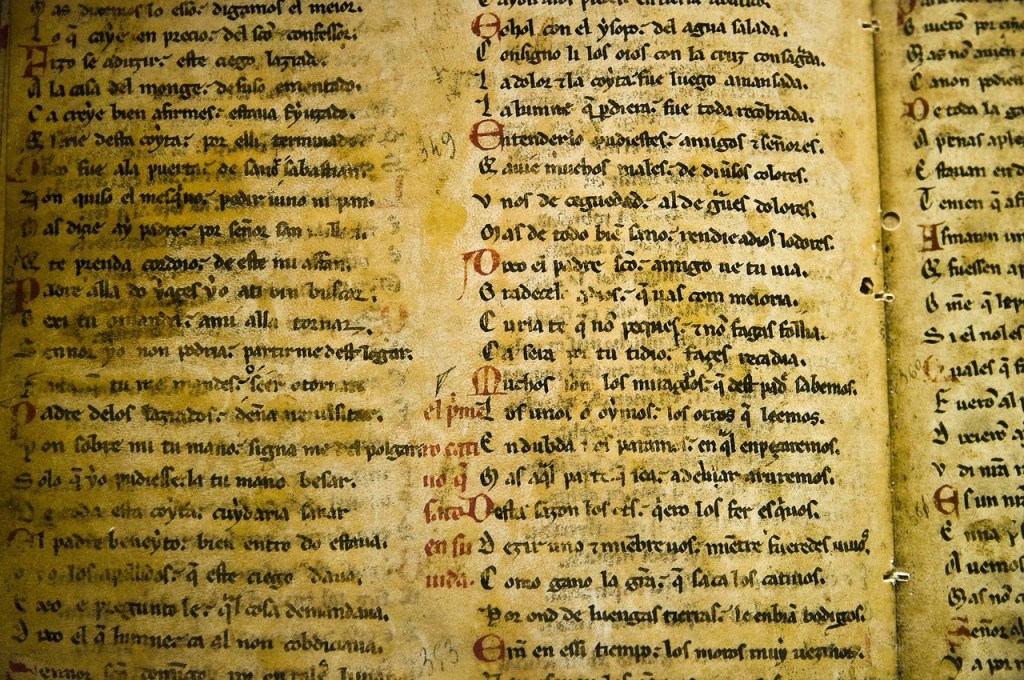

Think about the Buddhist practice of shakyō, where monks copy the Heart Sutra as a form of meditation. Or the medieval monks in Europe who spent their lives transcribing the Bible by hand, treating each word as a sacred act. Even today, some aspiring writers retype their favorite novels to understand the rhythm and feel of great writing. What ties all these practices together is a sense of purpose, mindfulness, and connection—qualities that can feel scarce in the digital age.

As a student, I turned to this practice myself. I copied the Bible, not just in one language but in both English and Japanese. For me, it felt like a form of Christian shakyō. I also copied essays by Carl Hilty in Japanese and Katherine Woods’ English translation of The Little Prince. With every stroke of the pen, I felt closer to the words, as if I could catch a glimpse of what the authors felt as they wrote them. The writings of James Allen also became a favorite for their classic beauty. Each piece offered not just inspiration but a sense of craftsmanship that made copying them a joy.

Writing by Hand: A Path to Reflection

Copying texts by hand might seem tedious or outdated, but that’s precisely the point. In a world of endless scrolling and multitasking, this practice forces us to slow down and focus. Instead of skimming over sentences or rushing through pages, copying makes us sit with each word and absorb it fully.

Take, for example, Katherine Woods’ classic translation of The Little Prince. One of its most famous lines reads:

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

When I wrote those words by hand, they came alive in a way they never had before. Writing them out made me pause and reflect on their meaning. What does it mean to “see with the heart”? What is “essential”? The simple act of copying turned those questions into a quiet meditation.

Writing by hand also connects us physically to the text. Typing is fast and efficient, but it can feel detached. With a pen in hand, each letter becomes an action, each sentence a commitment. This tactile engagement makes the words feel real, grounded, and personal.

Typing: A Modern Twist on an Old Practice

While writing by hand carries a unique charm, typing has emerged as a modern alternative for those looking to engage deeply with texts. Copying by typing can offer similar benefits, particularly for those who spend much of their day working on computers. It allows for the same kind of focus and immersion, with the added advantage of speed.

When I retyped texts by James Allen, I found that the rhythmic clicking of the keyboard helped me fall into a meditative flow. His classic style, with its wisdom and clarity, came to life as I typed each word. Typing doesn’t have the tactile satisfaction of writing by hand, but it still engages the mind and creates a sense of connection to the text.

For aspiring writers, copying by typing can also be a practical exercise. It’s a way to analyze structure, tone, and rhythm while maintaining the convenience of digital tools. Whether through pen or keyboard, the essence of the practice remains: slowing down to truly engage with the words.

A Universal Tradition

This practice of copying by hand spans cultures and religions. In Japan, shakyō is a spiritual exercise, where copying Buddhist scriptures becomes a path to mindfulness and understanding. Each brushstroke is deliberate, each character a prayer. In medieval Europe, monks didn’t just copy the Bible—they often adorned it with intricate illustrations, turning it into a work of art.

One of the most famous figures from this tradition is Thomas à Kempis, the author of The Imitation of Christ. He reportedly copied the entire Bible nine times. For him, it wasn’t just about preserving the text; it was about embodying its teachings through the act of writing. This idea of copying as devotion isn’t limited to religion, though. Even in the world of literature, writers have turned to this practice as a way to learn. Hunter S. Thompson famously retyped The Great Gatsby to capture the flow of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s prose. By copying, they didn’t just read the text—they lived it.

Learning Through Copying

There’s something magical about tracing another person’s words. It’s as if, for a moment, you step into their mind and feel what they felt when they wrote them. This practice doesn’t just help you understand the text—it helps you understand the writer’s choices, their rhythms, and even their struggles.

When I copied essays by Carl Hilty, I didn’t know German, the language in which they were originally written. But as I wrote out the Japanese translation, I felt connected to his thoughts in a way that reading alone couldn’t provide. The same happened with The Little Prince. Katherine Woods’ poetic translation, with its lyrical cadence, seemed to flow through me as I copied it word for word. The process made me appreciate the beauty of her language and the effort behind her choices.

For aspiring writers, this practice can be a game-changer. By copying the works of great authors, you get an insider’s view of their craft. You start to see how they build sentences, how they use punctuation, and how they shape their ideas. It’s not about imitating—it’s about learning and internalizing the tools that make their writing sing.

Slowing Down in a Fast World

In many ways, copying texts by hand feels like a form of rebellion against the speed of modern life. Everything today is about efficiency—how fast you can work, how quickly you can consume information. But copying slows you down. It asks you to focus on one thing at a time, to give it your full attention.

This slowness isn’t just a luxury; it’s a necessity. When you take the time to copy something by hand—or even by typing—you’re creating space for reflection and thought. You’re not just engaging with the text—you’re engaging with yourself. This is why practices like shakyō have endured for centuries. They remind us that meaning isn’t found in rushing from one thing to the next; it’s found in the quiet moments when we pause and take our time.

A Practice Worth Reviving

The act of copying texts by hand—or by typing—may seem like a relic of the past, but it has so much to offer us today. It’s a way to reconnect with the power of words, to slow down, and to engage more deeply with what we read and write. It’s a practice that bridges the gap between thought and action, mind and body.

For me, this practice has been a constant companion, shaping how I think and write. Whether it’s the Bible, essays by Carl Hilty, the poetic lines of The Little Prince, or the timeless wisdom of James Allen, copying these texts has taught me to see words not just as tools for communication but as doorways to understanding.

In a world where speed often trumps substance, this simple act of writing or typing offers something rare: a chance to slow down, reflect, and connect. It’s a reminder that the best things in life—whether they’re great books, meaningful ideas, or moments of clarity—are worth taking the time to appreciate.

Image by agusgeno