During my trip to Switzerland with my wife, we visited the majestic St. Pierre Cathedral in Geneva. Its towering presence, adorned with intricate exterior details, left me in awe as we stepped inside.

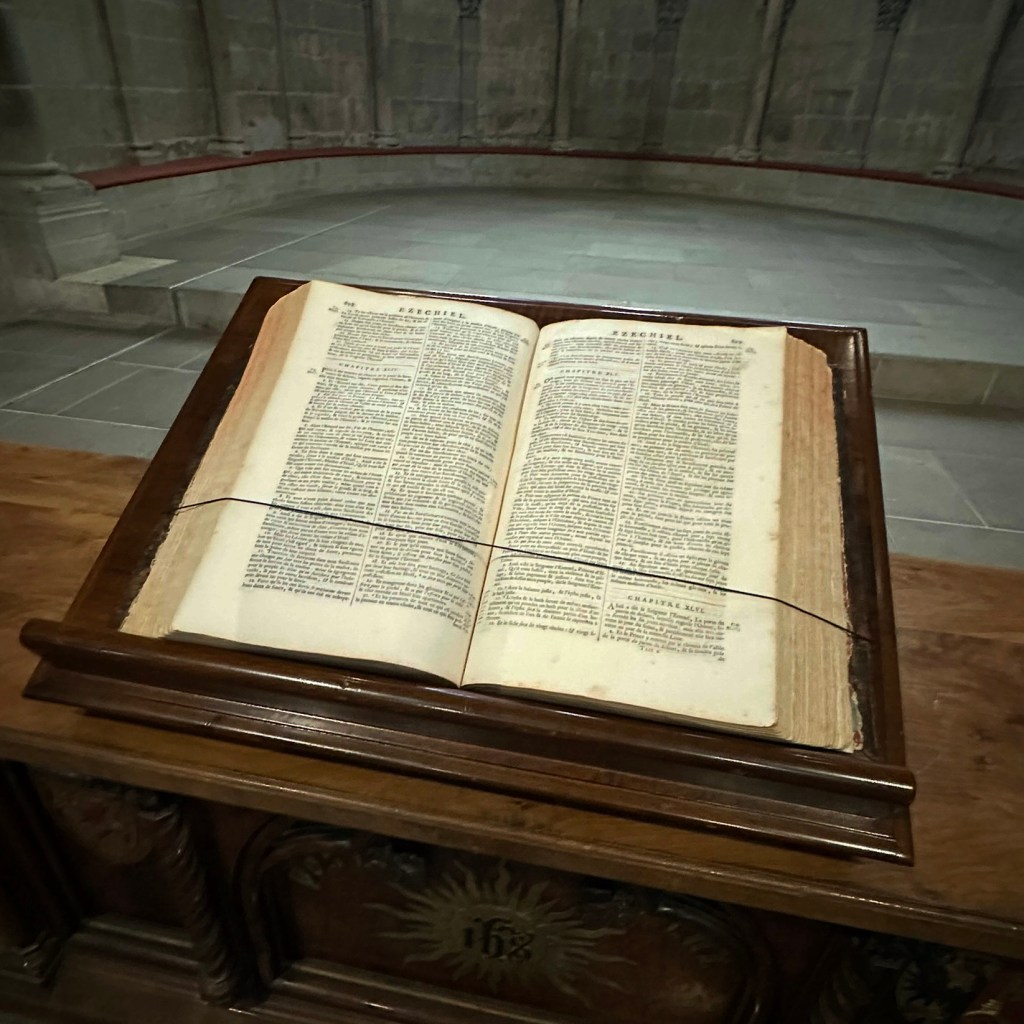

As I stood before the altar, I noticed something strikingly simple amidst the grandeur—there was only a single Bible placed on the altar. This contrast between the cathedral’s elaborate structure and the solitary Bible triggered a deep reflection within me. It made me think about the essence of Christian faith and how, at its core, it seems to strive toward simplicity.

This moment sparked a contemplation on the Protestant Reformation, particularly its emphasis on Sola Scriptura, the belief that Scripture alone is the authority for faith. The simplicity of the Bible at the altar seemed to mirror this idea, stripping away unnecessary rituals and doctrines to focus on the essentials of faith. It reminded me that, despite the complexity of religious traditions, there’s often a deeper call to return to the heart of spiritual life, where faith, rather than knowledge or practice, takes center stage.

As I reflected further, I realized that this minimalistic approach to faith is not confined to Protestantism. Even within Catholicism, with its monastic traditions of prayer and work, and in other religious traditions like Buddhism, there are similar efforts to distill faith to its purest form. Let’s explore this shared impulse across traditions—what I have come to call “religious minimalism”—and how it manifests in both Christian and Buddhist contexts.

Christian Minimalism

The Reformation in the 16th century was more than a historical event—it was a spiritual revolution aimed at returning to the basics of Christianity. At its heart, the Reformers sought to emphasize the core truths of faith, away from what they viewed as the excessive rituals and doctrines that had accumulated over time. The Five Solas—Sola Scriptura (Scripture alone), Sola Fide (faith alone), Sola Gratia (grace alone), Solus Christus (Christ alone), and Soli Deo Gloria (to the glory of God alone)—were foundational principles that aimed to simplify and clarify the Christian life.

Take, for example, Sola Scriptura. The idea that Scripture alone is the authority for faith and practice shifts the focus from tradition or ecclesiastical hierarchy to the written word. Yet, this wasn’t just a call to read the Bible; it was a profound statement about returning to the essentials. The stark architecture of Protestant churches like St. Pierre Cathedral in Geneva, with their austere interiors and focus on the Bible, reflects this theological minimalism. The focus here is not on grand rituals but on the core of faith itself—the word of God and the relationship of the believer to it.

Even within Catholicism, one can find a similar quest for simplicity. The life of monasteries, particularly in the Benedictine order with its motto of ora et labora (prayer and work), offers a parallel to Protestant minimalism. In the quiet life of prayer, manual labor, and contemplation, monks seek to live out the core of Christian devotion without the distractions of the outside world. Here, minimalism is less about theological reduction and more about lifestyle—an active choice to pursue simplicity in order to deepen one’s relationship with God. In both cases, the aim is the same: to focus on what truly matters.

Faith and Knowledge

A natural question that arises in the pursuit of simplicity is how much knowledge is necessary for true faith. Christianity, particularly in its intellectual traditions, has always placed a strong emphasis on learning—whether it be understanding the original languages of the Bible, grasping theological doctrines, or studying historical and cultural contexts. Yet, there is a tension between the acquisition of knowledge and the living out of faith.

Jesus Himself emphasized this tension when He spoke of welcoming the kingdom of God with the simplicity of a child. He said:

Truly I tell you, anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it. (Mark 10:15)

The simplicity of faith, characterized by trust and devotion, can sometimes stand in contrast to the complex theological systems that have developed over centuries. While it is certainly valuable to understand Scripture in its original Hebrew or Greek, or to study the philosophical underpinnings of Christian theology, this knowledge alone does not constitute faith. Knowing more can certainly enrich one’s spiritual life, but it is not the foundation of faith itself.

This brings us to the central question: How much do we need to know to live a faithful life? While the study of theology, philosophy, and history can deepen our understanding of Christianity, there is a danger in placing too much emphasis on knowledge at the expense of living out one’s beliefs. The pursuit of intellectual mastery, though valuable, should not overshadow the simplicity of trust in God and the call to love one’s neighbor. Christian minimalism, in this sense, is not an anti-intellectual stance but a reminder that knowledge is only a tool to deepen faith, not its essence.

The Verses for Minimalism

At the heart of Christian faith lies the Bible, which serves as the guide for many believers. When viewed through the lens of minimalism, it is not the vast quantity of Scripture but the distilled teachings that hold the most profound meaning. The Bible, though expansive, often focuses on key principles—love, faith, grace, and redemption—that form the foundation of Christian life. This is especially evident in the Gospels, where Jesus emphasizes the essentials of faith through simple yet transformative teachings.

One of the clearest examples of this minimalist approach is found in Jesus’ introduction of the Lord’s Prayer. In the Gospel of Matthew, He offers His disciples a simple prayer that encapsulates all aspects of a relationship with God: worship, daily provision, forgiveness, and guidance. The Lord’s Prayer stands as a concise model for Christian prayer, stripping down complex needs into a few essential requests, embodying the minimalistic focus on the essentials of faith.

Similarly, when asked about the greatest commandment, Jesus responded with a minimalistic yet profound answer:

Jesus replied: ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments. (Matthew 22:37-40)

In this moment, Jesus distilled the entire Jewish law into two commands, capturing the essence of faith in its most simplified form—love for God and love for others.

Paul’s Letters in the New Testament further echo this minimalist emphasis. For Paul, the core of Christian life was faith in Christ, not the detailed observance of religious laws. In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul writes:

Knowledge puffs up while love builds up. (1 Corinthians 8:1)

Paul points out that while knowledge can lead to pride, love nurtures true spiritual growth. His words serve as a reminder that the heart of Christianity lies not in intellectual mastery but in the expression of faith through love. He reinforces this sentiment in another letter, writing:

For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision has any value. The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love. (Galatians 5:6)

Paul reduces religious complexities to two essential elements—faith and love—demonstrating that the essence of Christianity is not in ritual or extensive knowledge but in living out one’s faith through acts of love and devotion.

Zen Minimalism

Turning to another tradition, we find a similar emphasis on simplicity in Zen Buddhism. Zen, particularly through its practices of meditation and the use of koans, seeks to transcend the limitations of language and knowledge. In contrast to traditions that emphasize scriptures and doctrinal study, Zen focuses on direct experience—on seeing reality as it is, without the filter of intellectual concepts. In this way, Zen minimalism is an effort to bypass the distractions of words and dive straight into the experience of enlightenment.

The famous Zen saying, “The finger pointing at the moon is not the moon,” captures this idea. Words and teachings are useful insofar as they guide the practitioner, but they are not the ultimate truth themselves. Zen seeks to avoid the indulgence in words and intellectualization that can distract one from the direct experience of reality. In this sense, Zen minimalism parallels the Reformation’s desire to strip away unnecessary doctrines and practices, seeking to connect directly with the core truth of the tradition.

Moreover, Zen’s focus on the monastic life is also a form of simplicity that echoes early Buddhist practice. In the Sangha, or the early Buddhist community, monks renounced worldly possessions and lived a simple life of meditation and mindfulness. This simplicity was not just about material renunciation, but about clearing the mind of distractions and focusing on the essential. In Zen, the monastic life serves the same purpose—creating an environment where the practitioner can focus solely on their spiritual practice without the distractions of daily life.

Religious Minimalism

What connects Christian minimalism and Zen minimalism is the shared human desire to return to the essence of spiritual life. Whether it is through the simplicity of Sola Scriptura or the direct experience of enlightenment in Zen, there is a universal impulse to move beyond the complexities of religious systems and focus on the core truths that guide human existence. This drive can be seen across traditions, making “religious minimalism” a useful term to describe this phenomenon.

In both traditions, simplicity is not a rejection of knowledge or tradition, but a conscious choice to prioritize the essentials. For Christians, this may mean focusing on the Bible, faith, and grace rather than on elaborate rituals or theological debates. For Buddhists, it means emphasizing direct experience over intellectual understanding. In both cases, the goal is the same: to create a space where the individual can connect with the divine, or with reality, in the most direct and meaningful way.

At its heart, religious minimalism is about finding clarity in faith. It asks us to reflect on what is truly necessary for a life of spiritual depth and to remove anything that distracts from that goal. In a world filled with complexity, religious minimalism offers a path to simplicity—not as a rejection of the world, but as a way to focus on what truly matters.

Simplicity and Depth

The movement toward religious minimalism, whether in Christianity or Buddhism, reflects a deep desire for clarity in faith. This effort to focus on the essentials—on what truly matters in spiritual life—speaks to a universal human impulse. From the simplicity of the Lord’s Prayer to the Zen practice of silent meditation, religious traditions across the world offer pathways to reconnect with the core truths that guide our lives.

Simplicity does not mean a lack of depth. On the contrary, the simplicity sought in religious minimalism is often a pathway to deeper spiritual understanding. By clearing away distractions, both intellectual and material, religious minimalism allows for a more profound engagement with faith. Whether through Christian or Buddhist lenses, the journey toward simplicity is ultimately a journey toward greater depth and meaning.