In the vast ocean of literary treasures, the “Konjaku Monogatarishū” (今昔物語集), or “An Anthology of Tales from the Past and Present,” stands as a beacon of Japan’s rich narrative heritage. Compiled in the late Heian period, this collection of over one thousand tales offers a window into the soul of medieval Japan, weaving stories that range from the profoundly spiritual to the mundanely human.

Among these narratives, one tale recently captured my attention anew — “A Husband Cutting Reeds.” Though centuries old, its themes resonate with a timeless quality, making it particularly poignant for readers who have witnessed the ebb and flow of life’s fortunes.

Let’s delve deeper into the historical essence of this ancient anthology and the enduring significance of “A Husband Cutting Reeds.” Through this exploration, I aim to uncover how a tale from a distant past can still mirror the universal human experience, offering insights that speak to our own lives today. This reflection is a journey into the heart of a story that transcends time and culture.

Historical Context

The Heian period (794 to 1185) in Japan was an era marked by cultural flourishing and artistic achievements. It was during this time that the “Konjaku Monogatarishū” was compiled, a monumental work that not only encapsulates the ethos of its era but also sets the stage for the future of Japanese literature. This anthology is a testament to the sophisticated court culture of Heian Japan, reflecting the intricate social structures, religious beliefs, and philosophical thoughts of the time.

The “Konjaku Monogatarishū,” meaning “An Anthology of Tales from the Past and Present,” comprises over a thousand tales that span various genres — folklore, anecdotes, religious narratives, and more. Its stories traverse geographical boundaries, originating from India, China, and Japan, showcasing a remarkable cultural exchange and the cosmopolitan nature of Heian society. This anthology serves as a crucial link between the oral storytelling traditions and the written literary culture that was emerging in Japan.

Its significance lies not only in its narrative diversity but also in its linguistic innovation. The tales were written in classical Japanese, a language that was still evolving, and they played a significant role in shaping the Japanese written tradition. The “Konjaku Monogatarishū” thus stands as a cornerstone in the history of Japanese literature, offering invaluable insights into the life and times of Heian Japan.

A Husband Cutting Reeds

“A Husband Cutting Reeds,” a story from the “Konjaku Monogatarishū,” unfolds in the culturally rich backdrop of Heian Japan. It tells the tale of an educated couple, neither destitute nor wealthy, whose lives are intertwined with love, ambition, and the realities of their modest means.

The husband, while deeply caring and devoted to his wife, is not just troubled by their continuous state of modest living but is also driven by a personal ambition for success. He grapples with the thought that their ongoing poverty might be linked to his own limitations or perhaps the dynamics of their relationship. In a mix of self-reflection and a desire to achieve more, he proposes the idea of separation. He believes that parting ways could potentially lead to better fortunes for both of them, especially hoping that his wife might find a life of greater comfort and happiness without him.

The wife, whose loyalty and contentment lie within the simplicity of their life together, initially resists the idea of separation. However, understanding her husband’s ambitions and his deep concern for her well-being, she reluctantly agrees, honoring both his aspirations and his affection for her.

As time passes, their lives diverge sharply. The wife, through a stroke of fate and remarriage, ascends to wealth and comfort, while the husband, in pursuit of his ambitions, finds himself descending into greater poverty, eventually working as reed-cutting for farmers. Their paths cross again in an unexpected encounter, with the husband oblivious to his former wife’s presence and her newfound prosperity.

Their reunion is silently underscored by an exchange of waka, traditional Japanese poetry, which becomes their mode of conveying deep, unspoken emotions. The husband’s verse reflects a mix of humility, sadness, and acknowledgment of their changed worlds, tinged with the lingering traces of his unfulfilled ambitions. The wife’s poetry resonates with sorrow and compassionate understanding, hinting at the complexity of their shared past and separate futures.

This encounter, laden with the weight of unexpressed feelings and unmet aspirations, concludes with the husband withdrawing quietly, a gesture of respect for their shared history and an acceptance of their current realities. The wife keeps this poignant meeting a secret for years, revealing only fragments in her later life. The story thus evolves into a profound commentary on the aspirations and sacrifices in love, the impact of economic realities on human relationships, and the enduring ironies of life.

The Power of Poetry

In “A Husband Cutting Reeds,” the exchange of waka, traditional Japanese poetry, plays a crucial role in expressing the profound emotions of the characters. Waka, with its structured 31-syllable format (5-7-5-7-7), is renowned for its ability to encapsulate complex emotions and thoughts, often utilizing symbolism and natural imagery.

The wife’s poem in hiragana and romanized Japanese:

あしからじとおもひてこそはわかれしかなどかなにはのうらにしもすむ

Ashikaraji to omoite koso wa wakare shi ka nado ka Naniwa no ura ni shimo sumu

Translated to:

Thinking it would not be amiss, we parted ways, yet why do I find you now cutting reeds, dwelling by Naniwa’s bays?

This poem uses the imagery of Naniwa’s shore and reed cutting to symbolize the husband’s decline, conveying her unexpected sorrow upon discovering his plight.

The husband’s response in hiragana and romanized Japanese:

きみなくてあしかりけりとおもふにはいとどなにはのうらぞすみうき

Kimi nakute ashikari keri to omou ni wa itodo Naniwa no ura zo sumi uki

Translated to:

Parting from you, I thought it was for the best, yet Naniwa’s shores, where I cut reeds, only deepen my unrest.

Here, Naniwa’s shores metaphorically express his deepened sense of loss and hardship after their separation.

Translating waka into English is challenging, as it involves capturing the original’s emotional depth and symbolism within different linguistic and cultural frameworks. The English versions presented are an earnest attempt to convey the essence of these poignant poems.

Through this exchange of waka, the story transcends its historical era, enabling the characters’ deep emotions to resonate with a contemporary audience. These poems serve as a silent yet emotionally charged dialogue, embodying the enduring bond and unspoken understanding between the husband and wife.

Reflections on Life

The tale of “A Husband Cutting Reeds” from the “Konjaku Monogatarishū” transcends its historical context to speak on universal themes that resonate deeply with contemporary readers. At its core, the story is a poignant exploration of love, loss, fate, and the enduring impact of choices we make.

Love and Sacrifice: The couple’s initial decision to part ways, driven by a mix of ambition and the hope for a better future for each other, poignantly illustrates the complexities of love. Their love is not just a romantic ideal but is interwoven with practical realities and sacrifices, reflecting a profound understanding of each other’s needs and aspirations.

The Irony of Fate: The stark contrast between the wife’s ascent to wealth and the husband’s descent into poverty after their separation underscores the unpredictable nature of fate. Their story is a reminder of life’s inherent uncertainties and the irony that sometimes, well-intentioned decisions lead to unintended consequences.

The Power of Unspoken Bonds: The silent exchange of poetry between the husband and wife highlights the depth of their unspoken bond. Despite the passage of time and the changes in their circumstances, their connection remains, communicated through the nuanced and symbolic language of waka.

Reflections on the Human Condition: The tale invites readers to reflect on the human condition — the intertwining of joy and sorrow, the impermanence of fortune, and the resilience of the human spirit in the face of life’s vicissitudes. It encourages a contemplation of our own life choices, the paths we take, and the enduring impact of our relationships.

“A Husband Cutting Reeds” is not just a story from a distant past; it is a narrative that holds a mirror to our own lives, encouraging introspection and a deeper understanding of the complexities of the human heart. It serves as a reminder that the themes of love, loss, and the twists of fate are as relevant today as they were in the Heian period.

Timeless Storytelling

In revisiting “A Husband Cutting Reeds” from the “Konjaku Monogatarishū,” we are reminded of the timeless nature of storytelling and its ability to connect us across centuries. This tale, though rooted in the Heian period, continues to echo in the hearts of modern readers, resonating with our own experiences and emotions.

The story is a testament to the enduring power of literature to transcend temporal and cultural boundaries. It invites us to explore the depths of human emotions, the complexities of relationships, and the often unpredictable journey of life. The subtle yet profound exchange of waka between the husband and wife in the story is particularly emblematic of the way our deepest feelings often find expression in art, in forms that surpass the limitations of time and language.

As we reflect on this tale, we are encouraged to ponder our own life stories, the decisions we make, and the paths we traverse. “A Husband Cutting Reeds” serves not just as a window into a distant past but also as a mirror reflecting our current lives, reminding us of the universality of human experiences — love and loss, success and failure, joy and sorrow.

This ancient narrative, with its rich symbolism and emotional depth, continues to offer valuable insights and lessons, proving that the core of human experience remains unchanged across ages. It stands as a poignant reminder of literature’s power to enlighten, to connect, and to endure.

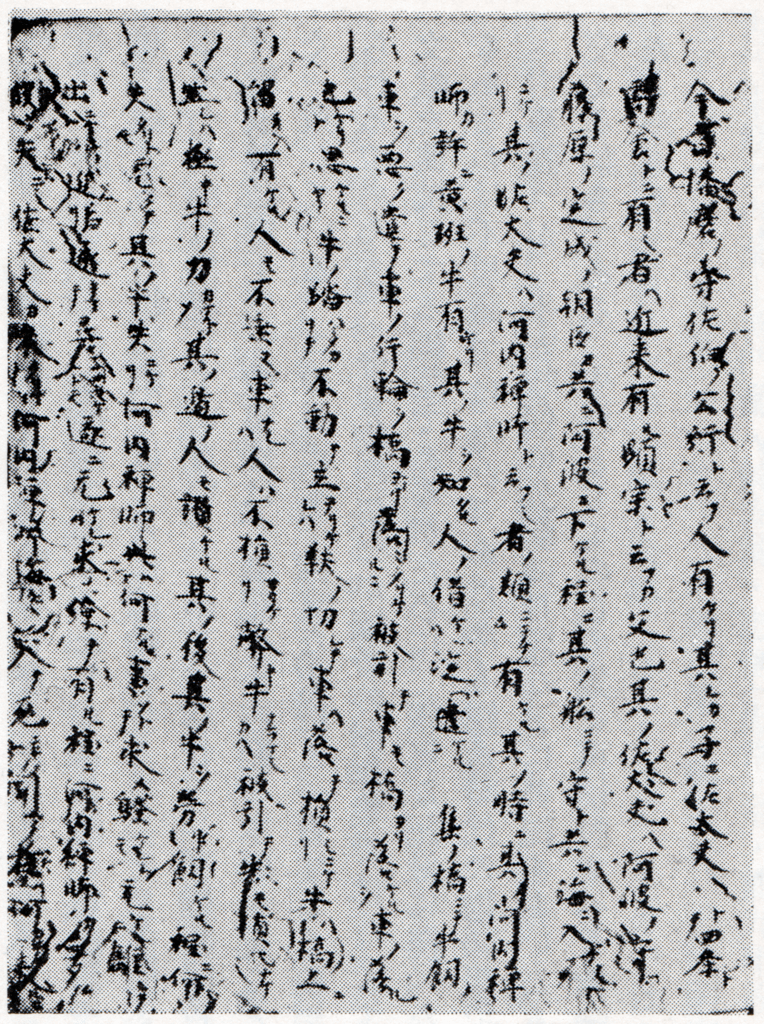

Image: Konjaku Monogatarishū Codex Suzuka