Most of us first encounter writing as an instrument. We write to communicate information, to persuade, to report, to fulfill assignments, to advance careers. Even when writing becomes creative, it often remains tied to outcome. A poem seeks publication. An essay seeks readership. A book seeks recognition. Writing is rarely neutral. It is usually directed toward something beyond itself.

There is nothing wrong with this. Writing has always served practical purposes. Laws are written. Letters are written. Arguments are written. Entire civilizations depend on the capacity to fix thought into language. Yet over time, a subtle question may arise. What happens when writing is no longer tied to immediate utility? What remains when it is detached from ambition, from visibility, even from persuasion?

In the nineteenth century, some artists proclaimed art for its own sake. The slogan resisted moral and political instrumentalization. It insisted that artistic creation need not justify itself through social function. Yet even this stance emerged within competitive cultural contexts. It was a position within a field, a statement among rivals.

Writing can pass through these layers. It can begin as necessity, mature into craft, and then move into something more interior. At a certain point, the act of writing may no longer feel like production. It becomes orientation. It is no longer about influence or achievement. It becomes a way of inhabiting one’s own existence.

When writing reaches that stage, it begins to resemble prayer.

The Layers of Prayer

Prayer carries many meanings. For some, it is a request. One asks for protection, success, healing, resolution. Prayer becomes a channel for hope. It aims at change.

There is another layer in which prayer seeks not specific outcomes but inner clarity. It asks for patience, strength, understanding. It is less transactional but still aspirational. It desires transformation, even if the transformation is internal.

Beneath these layers lies a more contemplative form. Prayer that does not ask for anything. Prayer that does not aim at improvement. It simply sustains relation. It is an act of attention directed toward something larger than oneself, or perhaps toward the sheer fact of being.

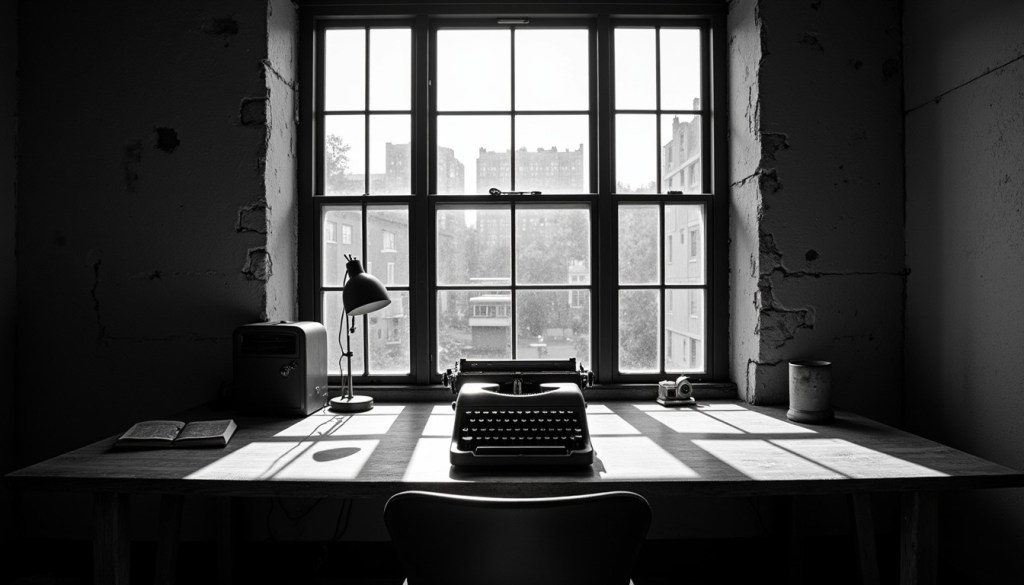

Writing, at its deepest, can align with this third form. The page becomes a space where attention is gathered. One writes not to request, not to demonstrate, but to remain in contact with reality. The act itself carries meaning, independent of external response.

In this sense, writing does not compete with prayer. It becomes prayer. It is an exercise of presence.

Practice Versus Production

Modern life trains us to think in terms of output. We measure productivity, track progress, count publications, monitor engagement. Writing fits neatly into this framework. It can be quantified and evaluated. How many essays were written? How many readers responded? How many citations accumulated?

Production invites measurement. It thrives on comparison. It asks whether the work achieved its intended effect.

Practice follows a different logic. It is repetitive, sometimes invisible, often unremarkable. It does not necessarily seek improvement in visible metrics. It seeks steadiness. A musician practices scales not for applause but for alignment. A runner maintains a daily route not for medals but for rhythm.

Writing as prayer belongs to the realm of practice. The writer returns to the page not because there is an audience waiting, but because the act itself stabilizes something within. The measure of success is not public reception. It is whether one showed up.

The metaphor of the Sunday painter illustrates this difference. The painter who works on weekends may harbor a subtle hope of recognition. Yet the deeper satisfaction lies in the act of painting itself. The brush moves across canvas because something in the painter must respond to color and form.

Writing can occupy that same space. It is not an escape from responsibility. It is a responsibility of another kind, a responsibility to one’s own interior coherence.

Attention as Devotion

At its core, writing as prayer is an act of attention. To name something carefully is to acknowledge its existence. To describe an experience with precision is to honor it. Language, when used deliberately, becomes a form of devotion.

Attention resists distraction. It resists the fragmentation of contemporary life. When one writes slowly, revising sentences, searching for clarity, one resists the pressure of immediacy. The page becomes a site of encounter rather than performance.

This encounter is not always dramatic. It may involve ordinary details, recurring questions, small insights that would otherwise dissolve into noise. Yet through writing, these fragments are gathered. They are not forced into grand narratives. They are simply held long enough to be seen.

Silence accompanies this process. Writing does not eliminate silence. It emerges from it. Words are shaped against a background of stillness. The discipline of revision reflects humility. The writer recognizes that first expressions are rarely complete. Refinement becomes part of the devotion.

In this way, writing ceases to be self expression in a narrow sense. It becomes participation in reality. The writer does not impose meaning. The writer listens, then responds.

Writing in the Age of AI

The presence of artificial intelligence introduces new possibilities and new temptations. Drafts can be generated quickly. Arguments can be reorganized instantly. The friction that once slowed writing diminishes.

This shift can encourage acceleration. If expression becomes easier, output may multiply. Essays can be produced in abundance. The risk is not that writing will disappear, but that it will become hollow through excess.

Yet AI can also function as companion rather than engine. It can ask questions, surface blind spots, offer alternative phrasing. Used thoughtfully, it does not replace attention. It can deepen it.

The center of writing as prayer remains human responsibility. The writer chooses to return. The writer chooses to reflect rather than merely generate. AI may assist in articulation, but it cannot supply devotion. It cannot substitute for presence.

In an environment saturated with assistance, fidelity becomes more important. Fidelity to the act, to the rhythm of returning, to the discipline of revision. Technology may lower barriers, but orientation still depends on intention.

The Continuity of a Life

To write as prayer is to accept continuity without guarantee. One may wonder how many essays remain before the end of life. The number is unknown. What remains certain is the possibility of returning once more to the page.

Recognition may or may not come. Readers may be few. The world may move in other directions. None of this invalidates the practice. Writing that arises from devotion does not require applause to sustain itself.

Over time, such writing accumulates not fame but coherence. It traces the arc of a life lived attentively. Each essay becomes less an achievement and more a moment of presence recorded.

Writing as prayer does not reject production. It simply refuses to be confined by it. It affirms that thinking is not merely a function of career, nor a strategy for advancement, but a dimension of living.

To sit down and write, again and again, without certainty of outcome, is an act of trust. It trusts that attention matters. It trusts that clarity, even if unseen by many, shapes the one who writes.

The page waits. The writer responds. The act itself is enough.

Image: StockCake