On December 30, 2025, news arrived that Tetsuzo Fuwa had died at the age of 95. It came quietly, as such news often does. There was no sudden rupture, no sense of shock. He had lived long, remained intellectually active, and already belonged more to history than to the present. And yet, his death did something unexpected. It reopened a century that many had assumed was already settled.

For those who lived through the decades when Fuwa, a long-time leader and chief theoretician of the Japanese Communist Party, and his predecessor Kenji Miyamoto were prominent public figures, the name still carries weight. Miyamoto, who shaped the party’s postwar identity, and Fuwa, who later gave it intellectual coherence and continuity, were not marginal actors in Japan’s political imagination. They evoke a time when ideology felt substantial, when political belief was not merely a preference but a worldview, and when history itself seemed to move with discernible direction.

In Japan, this was not a peripheral phenomenon. It shaped student movements, intellectual circles, publishing culture, and the self-understanding of what it meant to be progressive. Communism was not simply another political stance. It was a lens through which the present was judged and the future anticipated.

Remembering that period today is uneasy. It is tempting to call it a hopeful era, but hope built on partial knowledge carries a cost. The appeal of communism during the 1970s and 1980s rested not only on opposition to capitalism or American influence, but on a deeper conviction that history itself had a destination. Fuwa and Miyamoto were compelling not because they promised policy tweaks, but because they appeared to stand on the right side of time.

The passing of Fuwa makes it harder to keep that conviction at a safe distance. It invites recollection, and recollection brings with it unresolved questions. What exactly was believed then, and why did it feel so convincing.

When History Was Supposed to Move Forward

In those decades, communism was not simply a political option. It was a comprehensive narrative about how the world worked and where it was going. Young people in Japan, especially students and liberal intellectuals, did not admire the Soviet Union, China, or even North Korea merely as states. They admired them as historical projects. These societies appeared to embody a future already in motion, a future that capitalist democracies were destined to reach only belatedly, if at all.

The tragedies that would later define these regimes were not yet fully visible, or were treated as unfortunate deviations. The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were known in outline, but not in human detail. Cambodia remained largely outside the moral imagination. Where information did circulate, it was often framed as distortion, exaggeration, or unavoidable sacrifice within a grand process.

What mattered was not perfection but direction. History, it was believed, had laws. Capitalism contained contradictions that would intensify. Class struggle was not optional but structural. Socialism and eventually communism were not aspirations but outcomes. To oppose this trajectory was not merely to disagree politically, but to misunderstand reality itself.

This belief offered something rare and powerful. It relieved individuals of existential ambiguity. One did not need to invent meaning or negotiate plural values. Meaning was embedded in history. Action aligned with necessity. Commitment became virtue.

Looking back, it is difficult to decide whether these were good years. They were certainly intense, and intensity can feel like vitality. But intensity without self correction often postpones reckoning rather than preventing it.

Dialectical Materialism as an Operating System

At the center of this worldview lies dialectical materialism. It is often described as an ideology, but that description understates its role. Dialectical materialism functions less like a doctrine and more like an operating system.

An operating system does not dictate individual applications. It defines the environment in which applications run. It sets the grammar of possibility. In the same way, dialectical materialism defines what counts as reality, what counts as progress, and what counts as error. It determines the categories through which social phenomena are interpreted.

Within this system, historical failures do not invalidate the framework. They are explained as incorrect implementation, immature conditions, or distortion by hostile forces. The operating system itself remains intact. Critique is permitted, even encouraged, as long as it targets applications rather than architecture.

This is why communist parties can condemn Stalinism, criticize Maoist excesses, or distance themselves from foreign regimes without questioning the underlying worldview. The OS remains scientific, objective, and historically grounded. Only the apps malfunctioned.

Conflicts between communist parties follow this logic. They resemble denominational disputes more than empirical disagreements. Each claims fidelity to the same truth while accusing others of misinterpretation. Each believes it understands the dialectic more correctly. The debate is not whether the OS is valid, but who has implemented it faithfully.

This structure makes internal reform possible but external reflexivity rare.

Faith Without Transcendence

Dialectical materialism rejects religion, yet it fulfills many of the same functions. It offers a comprehensive explanation of the world, a moral hierarchy, and an ultimate horizon of meaning. History replaces providence. The proletariat replaces the chosen people. Revolution replaces salvation.

This does not make its adherents irrational. On the contrary, it attracts serious and intelligent individuals precisely because it promises coherence. Figures like Miyamoto and Fuwa were not dogmatists in the crude sense. They were rigorous thinkers, deeply engaged with theory, history, and international debate.

But intelligence, when fully invested within a closed system, sharpens internal consistency without guaranteeing external distance. The system claims to be meta already. It presents itself as the standpoint above ideology, the method that unmasks false consciousness. Once that claim is accepted, no further meta position is conceivable.

Those who question the operating system are not seen as offering alternative interpretations. They are seen as confused, ideological, or historically immature. Dialogue becomes difficult not because of hostility, but because the epistemic rules are already settled.

This is the quiet faith at the heart of communism. It is not devotional, but it is absolute.

After Disillusionment, an Aging Faith

Time did what critique alone could not. As information accumulated and regimes collapsed, many believers became disillusioned. The historical inevitability they trusted did not arrive. Or worse, it arrived in forms that demanded moral compromise.

Yet disillusionment did not operate evenly. Some left the worldview entirely. Others adjusted applications while preserving the operating system. This divergence helps explain a visible generational pattern in Japan today. Active self identified liberals are disproportionately older. Their political grammar was formed in an era when history still felt directional.

The Japanese Communist Party reflects this trajectory. It survived because it moderated itself. It rejected violent revolution, accepted electoral politics, and deliberately reduced charismatic leadership. It learned restraint, and restraint kept it alive.

But restraint did not include abandoning the operating system. The belief in historical necessity remains implicit. The future is still imagined as a resolution of contradictions rather than an open field of contingent outcomes.

Younger generations, shaped by fragmentation rather than grand narratives, find this grammar distant. They do not reject social justice, but they distrust inevitability. They do not assume history owes them validation.

Two Paths, One Inescapable Grammar

The contrast between the JCP and the Chinese Communist Party is instructive. On the surface, they appear radically different. One is cautious, marginal, and self limiting. The other is dominant, assertive, and unapologetic.

Yet both operate within the same ideological grammar. Both inherit the same operating system. The difference lies in how fully they commit to it.

The JCP restrains itself in the name of democratic coexistence. It limits charisma, disperses authority, and accepts marginality. The CCP asserts inevitability through power. It treats history as justification and discipline as virtue.

Neither escapes the underlying assumption that pluralism is temporary, that contradiction resolves into synthesis, and that history ultimately validates one path.

This shared grammar explains why critique between communist parties rarely reaches the deepest level. They argue over execution, not premise.

What Remains After Inevitability

The death of Fuwa marks more than the end of a life. It marks the passing of a generation that believed history could be read with confidence. That belief gave structure, purpose, and moral clarity. It also limited humility.

What remains is a question rather than an answer. What does politics look like when inevitability is no longer credible. What happens when history does not promise redemption.

Perhaps the future requires less certainty and more restraint. Less faith in synthesis and more tolerance for plurality. Less confidence that time is on one’s side, and more responsibility for what one does in the present.

Communist parties struggle today not because they lack intelligence or dedication, but because they must learn to live without the assurance that history itself is their ally. That is not a technical problem. It is an existential one.

And in that sense, Fuwa’s passing does not close a chapter. It leaves it open.

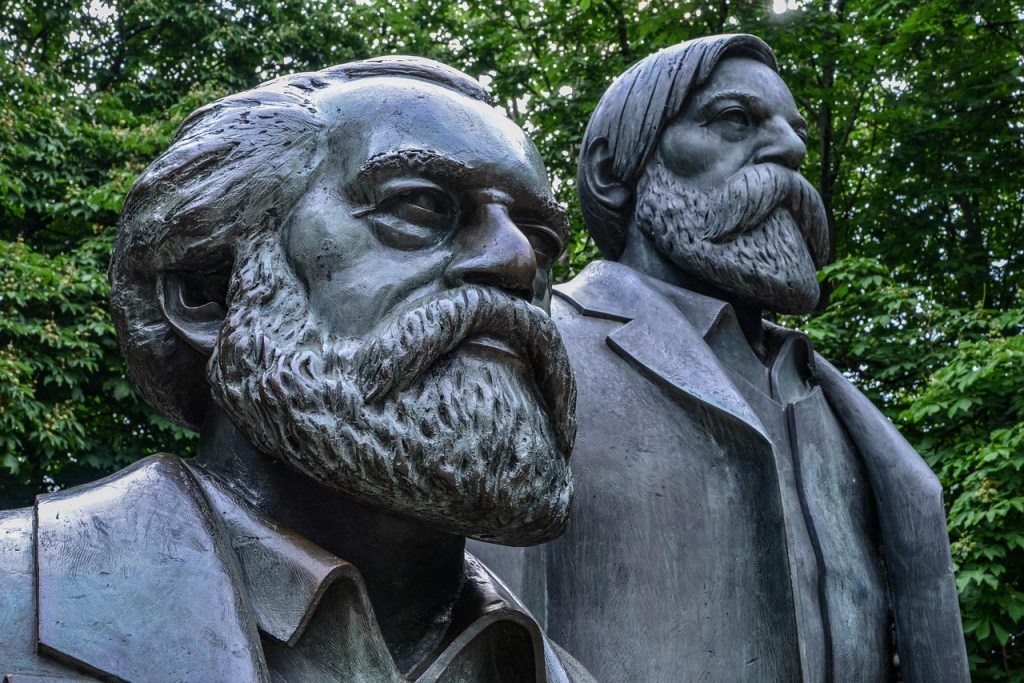

Image by wal_172619