I recently watched the film To Live (1994) and found myself deeply moved by it. The experience began with a simple surprise. I realized that the director of this heavy and emotionally charged work was Zhang Yimou. I knew him already from a very different period of life, through The Road Home (1999), a film I watched in my younger days. That earlier film felt gentle and sentimental, and I remember being touched by its quiet beauty. Returning to this director through To Live felt like meeting an old acquaintance again, but in a very different setting and at a very different depth.

The contrast between these two films opened something in me. To Live carries the weight of history in a very raw and intimate way. The Road Home carries emotion through memory, devotion, and rural simplicity. Yet both films have a thread that connects them. Both reveal the life of ordinary people and both treat human experience as something that can hold the fullness of joy and sorrow at the same time.

Watching To Live also brought back the uneasy feelings I often experience when reading about the history of China during the mid twentieth century. The Chinese Civil War, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution form a sequence of tragedies that are almost difficult to look at directly. Every time I try to understand these eras, I feel a mixture of sadness and disbelief. The political violence, the state induced famine, the erasure of culture and knowledge, and the dismantling of families all appear impossible for the modern mind to comprehend. Yet they happened in the lifetime of people still alive today.

The film made me reflect not only on those historical events but also on the contemporary reality of China. The era has changed, but several tensions remain the same. Censorship is still present. Critical incidents like the Tiananmen massacre remain forbidden to mention in public. People still live under a political system that demands loyalty as a condition for participation in public life. Watching To Live made me feel that the story of modern China is still unfinished. What Zhang Yimou once revealed through the Xu family still echoes in the present.

The Depth of Zhang Yimou’s Early Vision

Zhang Yimou’s early films reveal a director who knows how to reach the human core of a story. He is able to show the life of one family in a way that reflects the fate of an entire nation. This ability gives his early work a sense of scale that feels ancient, almost mythic. To Live is not a traditional historical film. It is a story that uses personal experience to reveal the weight of collective trauma. By focusing on the ordinary life of the Xu family, Zhang creates a window into the soul of twentieth century China.

Fugui and Jiazhen do not represent political groups or ideological positions. They represent survival, humility, humor, and the quiet strength that appears when everything else collapses. Their story becomes the story of millions of people who endured war, famine, political campaigns, and the unpredictable shift of social expectations. The film shows these events without exaggeration. It avoids sensationalism. It simply follows a family trying to live through circumstances entirely beyond their control.

The sense of epic scale arises not from grand scenes but from the careful attention to small details. Fugui’s shadow puppets, his losses, his mistakes, and his resilience all carry symbolic weight. The puppets mimic the movement of people who are controlled by distant forces. They remind us that political ideologies can turn entire populations into figures on a stage they did not choose. The intimate portrayal of this manipulation makes the story feel both personal and symbolic.

The film offers a study of tragedy that is also a study of love. Fugui’s transformation from a careless young man to a father trying to protect what remains of his family becomes a thread of human dignity. The profound pain of losing children, the absurdity of political slogans, and the quiet loyalty between husband and wife all create a form of beauty that comes from honesty rather than comfort. This honesty is what gives the film its emotional power.

Constraint and the Birth of Honest Art

It is striking that Zhang Yimou created his most powerful films during a period when he had very little room to speak openly. To Live was produced in a context of political pressure, and the consequences were severe. The film was banned in China. Zhang was forbidden to work freely for several years. Yet this period of difficulty was also the period of his greatest artistic depth. The tension between personal truth and external constraint created a level of creativity that is rare.

This is a paradox found throughout the history of art. When the environment restricts expression, artists must search for deeper and more precise ways to reveal truth. Zhang used metaphor, subtle symbolism, and the portrayal of ordinary life as a way to express political realities. He could not present direct criticism, so he turned to the power of narrative. He allowed the story to speak for itself, and this silence became a form of resistance.

The director worked with limited resources. There were no large sets or spectacular scenes. The narrative depended on acting, framing, patience, and emotional clarity. These limitations gave the film a sense of quiet strength. They forced Zhang to trust the viewer to see meaning in details. The old courtyard, the handmade puppets, the sound of children running, and the silence that follows political slogans all carry significance.

The Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution are not explained in the film. They simply happen. This is how ordinary people experience history. They do not have discussions about ideology. They see the consequences in daily life. They face shortages, rules, violence, and fear. The simplicity of this portrayal makes the film more honest than any documentary or historical analysis could ever be.

Zhang Yimou’s early success therefore came not from freedom but from pressure. The danger made him attentive to the inner meaning of life. The fear of punishment sharpened his sense of responsibility. It produced a level of storytelling where every scene carries emotional weight. The constraint did not silence him. It forced him to find a deeper voice.

The Shift from Honest Storytelling to Grand Spectacle

When Zhang Yimou returned to filmmaking after his period of punishment, he did so with a different approach. The Road Home was a gentle and safe story. It presented rural life through the lens of memory and devotion. It offered beauty without political tension. The film allowed him to work again and allowed the authorities to accept him as a worthy representative of Chinese culture.

This return opened the path to a new stage of his career. Zhang became known for grand productions with elaborate costumes, large battle scenes, and striking choreography. Films like Hero, House of Flying Daggers, and Curse of the Golden Flower displayed a mastery of color and movement. He showed a capacity to build entire worlds on the screen. These works established him as a global figure in cinema.

The climax of this transformation came when he directed the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics in 2008. That event was a stunning display of unity, precision, and cultural pride. It showed the technical skill and visual imagination that Zhang possessed. It also signaled his full acceptance by the state. He was no longer a troublesome artist. He had become a national symbol.

Yet the shift to grand spectacle came with a cost. The films became larger and more visually impressive, but they lost the quiet force that once defined his storytelling. The earlier human struggles that revealed truth were replaced by stylized scenes that relied on visual pleasure. The emotional resonance weakened. The sense of epic scale remained, but the inner epic faded.

This change reflects a deeper reality about artistic creation. When an artist becomes tied to national representation, the priorities shift. The goal is no longer to reveal truth but to display unity, pride, and beauty. When political constraints remain but suffering becomes less visible, the tendency is to produce work that entertains rather than challenges. Spectacle replaces honesty. The grand scenes rise, but the human core grows thinner.

The Paradox of Success and Silence

Zhang Yimou’s career reveals a paradox that often appears in societies with limited freedom. Success becomes a cage. Once the artist achieves recognition, the political environment expects loyalty and caution. The space to tell painful truths becomes smaller. The public role grows, but the private freedom contracts.

This creates a tension between what an artist can do and what the political system encourages. The artist is asked to celebrate culture rather than question injustice. The early films that dealt with human suffering, moral ambiguity, and political chaos become risky. The safe path lies in beauty, nostalgia, patriotism, and mythic storytelling.

This is why Zhang’s early films contain a form of beauty that is absent in his later work. The earlier films were created through risk and sincerity. They were grounded in human experience. They touched the viewer because they were rooted in truth. The later films display skill, but they do not confront the underlying tensions of life under a single party system.

The paradox becomes even deeper when we consider the ongoing situation in China. The country has become economically affluent, yet political control remains strict. The government continues to censor information about Tiananmen and other sensitive events. The internet is filtered. Social media is monitored. People must be careful with words even in private conversations.

In this environment, the need for honest art is greater than ever. Yet the artists with the technical skill and visibility to create powerful work are often those who have already been drawn into the circle of official acceptance. Their freedom to express deep truths becomes limited. Their work becomes safer and more ceremonial. The paradox becomes painful to observe.

Modern China and the Stories That Still Need To Be Told

Although China has changed dramatically since the events portrayed in To Live, several aspects of life remain shaped by silence. Contemporary China faces a different kind of struggle. The suffering is no longer found in famine or war. It is found in psychological pressure, uncertainty, loss of memory, and the invisible weight of political expectations.

There are millions of migrant workers who build the cities but rarely feel at home in them. There are elderly people in rural areas who live alone while their children work in distant cities. There are families who carry unspoken memories of Tiananmen or the Cultural Revolution but cannot share them openly. There are young people who grow up in a digital world shaped by surveillance and filtered information.

These stories contain the potential for a new epic. The form may be different, but the essence is the same. It is the quiet struggle of ordinary people who try to build a life within a system that shapes their choices. A modern filmmaker may not be able to show political violence directly, but the truth can appear in smaller scenes. A conversation at a dinner table. A father who avoids a certain topic. A teenager who searches for something that cannot be found online. A grandmother who remembers a past that is no longer allowed to exist in textbooks.

These small gestures reveal the tension between memory and silence. They show the impact of control on human relationships. They show the inner world that forms when people must pretend in public and feel in private. These are the elements of a new epic. Not the epic of war, but the epic of endurance.

The next great Chinese storyteller will not emerge from the celebrated circles of the film industry. They will appear quietly, perhaps with small independent projects or films produced with minimal budgets. They will use simplicity as Zhang once did. They will focus on one family or one community. They will show life as it is lived under the surface. They will reveal the truth that cannot be spoken.

The Search for New Voices of Honesty

The desire to see new filmmakers who can reveal the inner world of modern China is a natural one. Zhang Yimou’s early films set a standard for emotional truth that many viewers still long for. The ability to present life through a single family and make it feel universal is rare. It requires sensitivity, courage, and a deep understanding of human nature.

The next storyteller will need to work with subtlety. They will need to rely on atmosphere, silence, and gestures rather than direct statements. They will need to use metaphor and ambiguity. They will need to trust that the viewer is capable of understanding what is not openly shown. In a system where direct criticism is dangerous, the strength of art comes from its ability to reveal truth without naming it.

This kind of storytelling is still possible. It can appear in documentaries, independent films, or even online works. It can also appear in diaspora communities where people have more freedom to express their experiences. Yet the heart of the next epic will likely come from someone who lives within the tension of modern China. Someone who sees the reality of daily life. Someone who feels both loyalty and frustration. Someone who carries the stories of their family and their community.

The power of epic storytelling does not depend on scale. It depends on truth. A small apartment in Shanghai or a rural village in Sichuan can become the stage of a profound narrative if the filmmaker knows how to see the humanity within it.

Epic, Tragedy, and the Beauty of Honesty

The journey from To Live to The Road Home and then to Zhang Yimou’s later films reveals a lesson about art and society. When an artist is close to the truth, even if the environment is harsh, the art gains strength. When an artist becomes comfortable and publicly celebrated, especially in a controlled society, the art may lose some of its depth.

This does not diminish Zhang Yimou’s talent. His skill in visual expression remains remarkable. His ability to work with color, movement, and atmosphere continues to impress. What his career reveals, however, is the fragile connection between artistic honesty and the environment that surrounds it.

To Live moved me because it treated suffering with respect. It did not dramatize pain for its own sake. It showed the quiet dignity of people who lived through unimaginable events. It reminded me that tragedy can reveal the most human qualities. The Road Home moved me for a different reason. It showed that memory and love can create a form of beauty that feels timeless. Both films reflect the inner epic that Zhang Yimou once carried.

The need for such inner epic remains present in modern China. The harsh tragedies of the past have given way to the quiet tension of the present. People still live between pressure and hope. They still navigate silence and memory. They still carry stories that cannot be spoken but can still be shown through art.

I hope to see new filmmakers who can express these realities with honesty. I hope to see stories that treat ordinary life with dignity. I hope to see a new myth for a new era, grounded in the truth of individual lives. Zhang Yimou’s early films remind us that this is possible. They show that the human spirit can survive even in the darkest times. They show that art can reveal what politics tries to hide.

The next epic will not come from grand scenes or spectacular visuals. It will come from a simple story told with clarity and compassion. It will come from someone who sees the world with both tenderness and courage. When that happens, the story of modern China will continue, not through slogans or state ceremonies, but through the quiet resilience of ordinary people who keep living, just as the Xu family did.

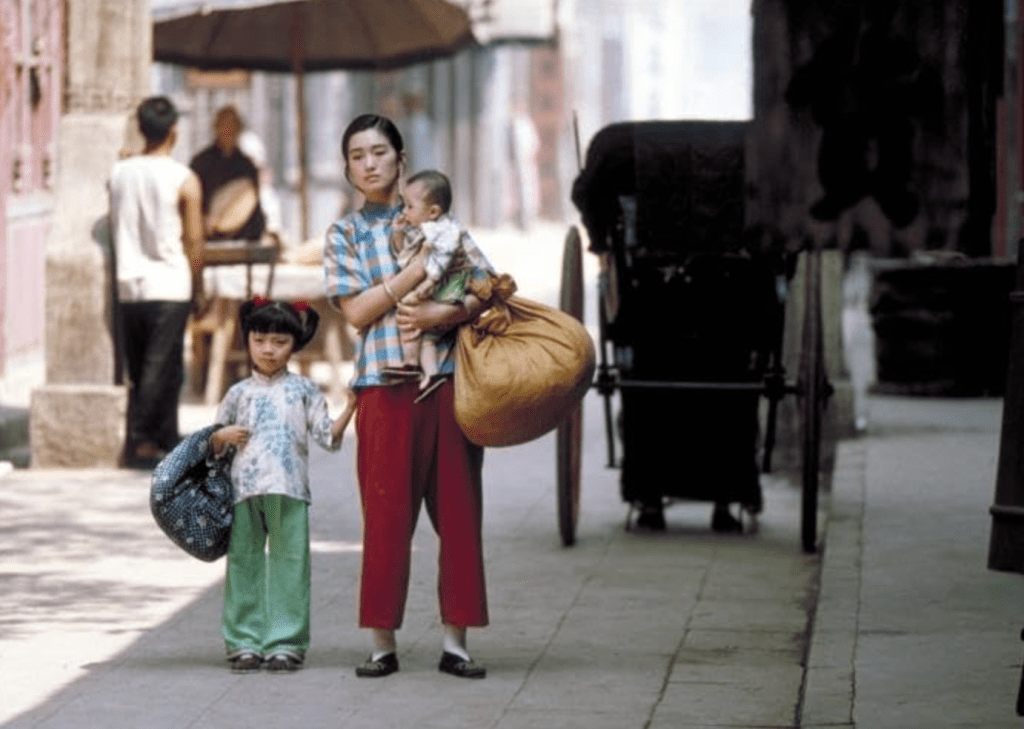

Image: Stockcake