There is a curious feeling that arises when we look at old ideas of the future. A silver robot with bulbous eyes, a rocket that looks like a shiny needle, and a city filled with floating cars and chrome. These images were created by people who looked ahead with genuine excitement. Yet when we see them now, we feel a kind of nostalgia. The strange part is that we are feeling nostalgia for something that never actually happened. The future they imagined has already become the past that we remember.

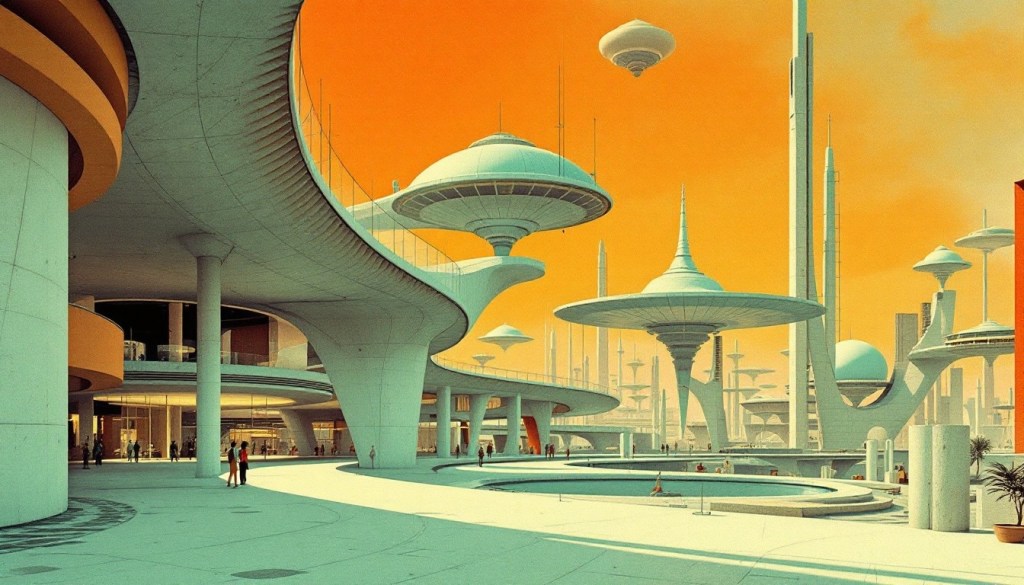

Retrofuturism describes that emotional twist. It refers to how the past imagined the future, especially during times of innovation and hope. When we see those playful visions, we sense the optimism of the people who created them. Their future looked bright and full of wonder. Even if they guessed wrong, they guessed with confidence that progress would make life magical.

This is why retrofuture artworks and objects feel warm. They capture imaginations at a time when humanity believed that tomorrow would always be better. The excitement of space travel, new machines, and friendly robots still echoes inside them. We look back not only at the designs, but at the promises they represent.

The Early Futures, Organic Curves and Mechanical Minds

In the nineteenth century, the world was filled with gears, levers, steam engines, and metal clangs. Machines were alive with motion. When writers and artists tried to imagine the future, they naturally pictured more of the same. They saw machines that were larger, faster, and more powerful. Robots looked like walking factories. Computers looked like huge mechanical brains. Every technological dream was shaped by a mechanical worldview.

This is not surprising. Imagination often grows from familiar tools. If someone in 1870 thought of a robot, that robot moved with gears because that was what a machine did. If someone in 1920 drew a computer of the future, it was a towering object with reels and blinking lights, because information and electricity seemed like physical forces that required physical space.

The shapes of those futuristic designs reflected something emotional as well. Curves dominated many early visions. Spaceships looked like eggs or ocean creatures. Alien planets were full of swirling forms. There was a sense of life blooming inside the mechanical age. These shapes suggested abundance and mystery, a future that would feel like nature and technology growing together.

Even now, when we look at retro posters or vintage sci fi films, their curves invite us to dream. They do not try to be realistic. They try to inspire. At that time, the future was not just a destination. It was a fantasy playground.

A New Realism, 2001, Star Wars, and the Rise of Functional Futures

Everything changed in the late twentieth century. Cinema and new scientific understanding pushed futuristic imagination into a new form. When 2001: A Space Odyssey arrived, audiences were shocked by how real everything looked. The spacecraft did not resemble elegant sea creatures. They looked like engineering products. Their corners were sharp. Their surfaces were plain. Their movements felt bound by gravity and physics. The film did not show imagination breaking free. It showed imagination accepting reality.

Then Star Wars arrived and added another revelation. In that world, spaceships were not shiny and perfect. They were scratched. They had dents and dirt. Technology looked used and worn. This felt like the future, but it also felt like history. It was a future that had grown old already.

The shift from curves to straight lines was more than an artistic trend. It represented a change in confidence. Technology was no longer a dream. It was becoming everyday life. People could finally picture the future not as a miracle, but as a continuation of what they already understood.

This shift reduced the emotional weirdness that earlier visions had. The future became believable. Yet as a result, many people might say it also became less poetic.

Curves and Lines in Cultural History

The alternation between curves and straight lines appears again and again across history. Art movements swing like a pendulum, shifting between rational structure and emotional expression. It is almost as if humanity cannot remain in one mode for too long. When people live in an age of strict precision, they begin to crave playfulness. When everything becomes too decorative or chaotic, society reaches back for form and order.

In architecture, Art Nouveau celebrated organic lines, flowing patterns, and the presence of nature within human spaces. Later, Modernism took away almost every ornament, leaving structures that stood as clean and geometric expressions of function. Brutalism pushed even further into concrete blocks and heavy shapes. These changes reveal how architecture responds not only to materials or technology, but also to shifting feelings about what it means to live a good and modern life.

Music reflects a similar rhythm. Baroque compositions by Bach feel like finely built structures, where every part follows a clear logic. The Romantic era that followed embraced emotional breadth and passionate curves within sound. Even without looking at buildings or paintings, we can hear the oscillation between order and exuberance.

Philosophy shows the same dynamic in another form. Nietzsche described Greek culture through the tension between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Apollo represented reason, symmetry, clarity, and restraint. Dionysus represented energy, passion, unpredictability, and organic vitality. These two forces, according to Nietzsche, must constantly balance each other. This ancient binary mirrors what we continue to see in design and art. Straight lines often express the Apollonian desire for structure. Curves often express the Dionysian energy of life.

Japanese anime demonstrates this duality in a fictional world. In Gundam, the Earth Federation uses machines built with straight armor panels and hard lines, expressing stability and control. Zeon uses mobile suits like the Zaku that look rounder and more biological, hinting at an instinctive style of power. It is the same symbolic contrast, now appearing in robots on a cosmic battlefield.

When we notice this recurring pattern, it feels almost archetypal. Humanity keeps moving between order and imagination, like breathing in and out. Straight lines and curves become more than design choices. They become expressions of how people understand themselves and their possibilities at any moment in history.

Retrofuturism as a Record of Cognitive Limits

Perhaps the most intriguing part of retrofuturism is what it reveals about how people thought. Those old future designs show the edges of imagination. It is not that people of the past lacked creativity. They simply could not imagine what they did not yet know.

When the Industrial Revolution defined machines as gears and pistons, futuristic machines were imagined with the same rules. When early computers filled rooms with massive cabinets, future computers were imagined as even bigger. The very idea of shrinking technology would have felt impossible because miniaturization had not yet entered the mind.

Retrofuturism shows how deeply our own present conditions shape what we think is possible. People cannot picture a future that is too different from their current understanding. They predict growth, but they rarely predict transformation.

For this reason, retrofuture imagery is like a photograph of the limits of collective imagination at a given moment. It is a reminder that every generation thinks it can see the horizon. Only later do we discover that the horizon had other horizons beyond it.

The Evolution of the Machine Mind

Technology does more than expand convenience. It also expands imagination. At the beginning of computing, people thought intelligence required big machinery. A thinking device must be large because they associated power with size. Vacuum tubes and giant panels created the mental model of the future brain.

Then the transistor and the microchip arrived, and everything began to shrink. A computer no longer needed the space of a building. It could fit on a desk. Eventually, it could fit in a pocket. The moment we understood that intelligence could be small, our imagination adjusted. Sci fi robots became slim and elegant. Futuristic interfaces became thin, quiet, and invisible.

Today, we are reaching another cognitive boundary. Artificial intelligence is powerful, but it relies on enormous servers and tremendous energy consumption. We assume AI needs electric force that greatly exceeds human levels. We imagine AI factories where giant cooling systems must maintain hardware that thinks day and night. This assumption shapes our future visions. They show a world with machines that glow with data, fill cities with processing centers, and consume electricity like oxygen.

Yet our own biological brain does something astonishing. It performs complex reasoning, memory, emotional response, and creativity while using only as much power as a small light bulb. It relies on chemical signals and delicate structures. It needs no giant cooling fans.

One day, future scientists might look at our data centers and smile. They might say that we were building steam engines for the mind. They may have discovered neural architectures that require no massive electrical infrastructure. They may have found ways to let intelligence grow like a plant.

If such breakthroughs occur, everything we imagine now will look as outdated as a wind up robot.

The Nostalgia of Broken Futures

Why do retrofuture images move us emotionally? One reason is that they capture the dreams of an age that believed in technology as a friend. When astronauts first looked at the Moon, many believed that cities on Mars would not be far behind. Robots would take care of housework. Cars would fly. Work would be easier. Life would be sweeter.

That sense of wonder feels rare today. We live in a time where the future sometimes feels heavy rather than hopeful. People worry about climate change, economic inequality, and the speed of technological disruption. Dystopias dominate our popular imagination. Our future stories are filled with fear rather than joy.

When we look at a 1950s vision of tomorrow, we feel the absence of that optimism in our current world. We long for the excitement of possibility. We remember that imagination once felt like a celebration, not a warning.

It is not only nostalgia for the style of the past. It is nostalgia for the belief that humanity could shape the future with confidence and creativity.

Our Own Retrofuture

It is interesting to realize that the way we imagine the future today will one day seem equally old fashioned. Our sleek phones, our self driving cars, our powerful AI algorithms, and our enormous rockets might appear slow or crude to the eyes of future generations.

Someone in the next century may visit a museum that shows a Tesla Cybertruck. They might laugh softly and admire its effort to look futuristic with straight metallic forms. They might see our smart devices and large screens as bulky, just as we see retro computers with giant knobs and glass tubes.

The same perspective might apply to architecture. Brutalist buildings and modern boxes of glass were created to look fresh and forward looking. Yet someday the skyline of New York or Tokyo might feel like an outdated dream of progress. Future structures might grow and adapt like coral instead of stacking concrete into rigid shapes.

Even our understanding of artificial intelligence will look temporary. We might be proud that we created neural networks modeled after the brain. Yet future scientists may discover that intelligence does not need to follow biological neural patterns at all. They may have solved cognition with methods we cannot yet imagine.

This humbling thought brings comfort. It shows that the future is always larger than our minds. Our imagination is a step forward, but never the final answer.

The Future as a Moving Horizon

Retrofuturism reminds us that creativity has a history. What seems revolutionary today will soon be absorbed into the ordinary flow of life. Every age imagines tomorrow through the lens of its own technology, materials, and feelings. That imagination stretches outward, but only as far as the present moment allows.

There is beauty in this limitation. It means humanity keeps discovering new ways to think. Design evolves as new possibilities become visible. Curves and lines take turns. Biology and machinery change roles. Science fiction and science exchange seats again and again.

Whenever we smile at an old idea of the future, we are also smiling at the courage of past dreamers. They tried to picture a world they would never see. They reached beyond their knowledge because they believed something exciting waited ahead.

We continue that same effort today. Even if our predictions become the next retrofuture, the act of imagining keeps us alive to possibility. The horizon keeps moving, and so does our ability to follow it.

The greatest value of retrofuturism might be this gentle reminder. The future is always ahead of thought. Our limitations today will become yesterday’s mistakes. Yet within each mistake is a story of hope. We should keep dreaming, not because we expect to be right, but because dreaming itself pushes the limits of what will be possible.

Image: Stockcake