Imagine a Christian in quiet prayer, repeating the familiar words of the Lord’s Prayer. Everything flows as it has for centuries, until the final line comes. “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen.” In a modern translation of the Bible, the eyes search for it but find nothing. The line that once crowned every recitation is gone, reduced to a footnote or left out entirely. It is a small omission, yet for many, it feels like the closing gate of a tradition that has shaped faith itself.

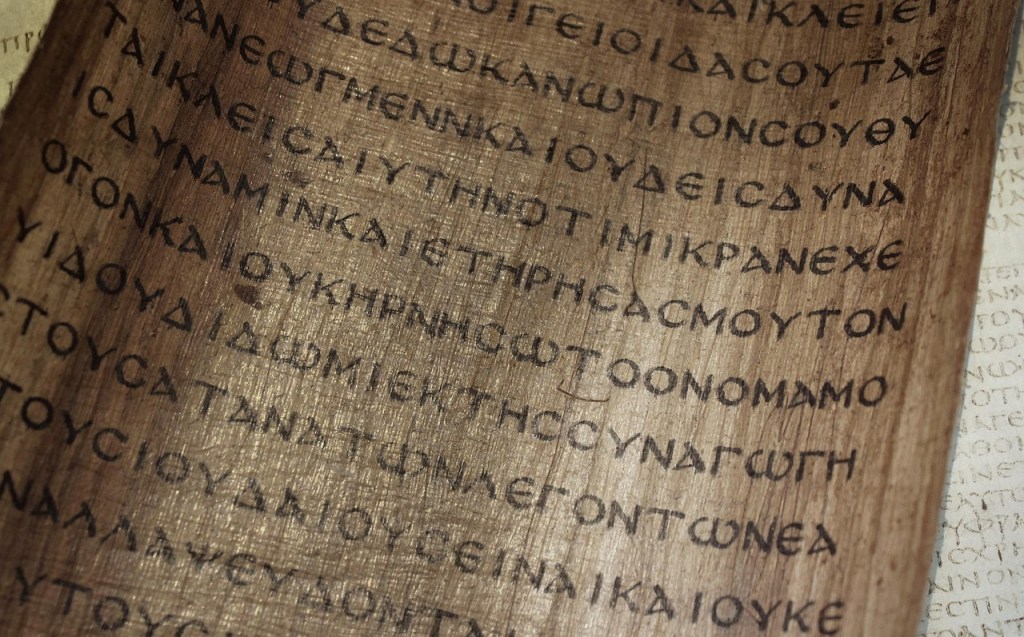

This absence reveals more than textual difference. It points to a deeper divide within the Christian world, a silent boundary separating two understandings of Scripture. On one side stands the Textus Receptus, the “Received Text,” carried through centuries of worship, copied by the hands of believers, and honored by reformers who believed that God had preserved His Word through the life of the Church. On the other side stand the modern critical editions, built from ancient manuscripts recovered by archaeology, refined by scholarly judgment, and revered for their historical proximity to the original writings.

The missing line in the Lord’s Prayer is only one example of many. There are other verses, such as the longer ending of Mark’s Gospel, the account of the woman caught in adultery in John, and the Trinitarian phrase in First John, that differ between traditional and modern texts. Each of these differences opens the same question in new form: is divine truth best found in what was earliest or in what was faithfully preserved? Beneath all these textual variations lies the same deeper issue, the tension between preservation and recovery, between the living voice of tradition and the academic search for origins.

The Birth of a Received Text

The story of the Textus Receptus begins in the sixteenth century with Desiderius Erasmus, the brilliant Dutch humanist who compiled and printed the first Greek New Testament in 1516. His edition, drawn from a handful of Byzantine manuscripts, was not perfect, yet it made Scripture visible and tangible in a way never seen before. From that work came later editions, and together they formed the foundation of the Reformation’s Bibles; the King James Version, the Luther Bible, and others that shaped the modern Christian imagination.

What made the Textus Receptus special was not only its words but the spirit of trust that surrounded it. It was seen not as an archaeological artifact but as a living inheritance. The Church had copied, preached, and sung from these texts for centuries. To many believers, that continuity was not a coincidence but evidence of divine providence. God, in their view, had preserved His Word through the common faith of His people, guiding it through history as part of His grace.

This understanding gave the Bible a kind of sacred maturity. It was not merely a document frozen in time but a voice tested and confirmed through generations. Its authority came not from how old its manuscripts were, but from how deeply they had entered the soul of the Church. To open the pages of a Bible based on the Textus Receptus was to join an unbroken chain of faith, one that stretched from the apostles through the Reformers and beyond.

The Doxology That Disappeared

The missing doxology in Matthew 6:13 is a small but revealing example of this divide. “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen.” For centuries, those words have concluded the Lord’s Prayer in both private devotion and public worship. Their rhythm mirrors the final notes of praise that echo throughout the Psalms, turning prayer into thanksgiving. Yet in most modern translations, this line is absent or enclosed in brackets, with a note explaining that the oldest manuscripts do not contain it.

For many, this omission feels more than technical. It touches the core of devotion. The doxology’s cadence is woven into Christian consciousness, repeated by children and monks, whispered by the dying. To see it missing on the printed page feels as if the voice of worship has been interrupted. The words are not just a liturgical flourish but a theological statement, affirming that all power and glory belong to God alone.

And yet, the doxology is only one face of a wider issue. The same pattern appears in other parts of Scripture. Some verses that once declared the deity of Christ, the ministry of angels, or the witness of the Spirit now appear in brackets or footnotes in modern translations. In Mark’s Gospel, the final resurrection appearances are questioned. In John’s Gospel, the story of the woman taken in adultery is moved or marked as uncertain. In First John, the clear Trinitarian line about the Father, Word, and Spirit agreeing in one has vanished entirely from many editions. Each of these examples touches something more than textual history; they touch the believer’s sense of what has been handed down as sacred truth.

Some churches have resolved the tension by separating text from tradition. They recite the doxology and cherish these familiar stories in worship even when they are absent from the printed Bible. Others accept their omission, trusting that the essential meaning of the Gospel remains. Still, for many believers, these variations are not merely academic matters. They represent a felt rupture between the faith that was lived and the faith that is now analyzed.

Two Theologies of Preservation

At the heart of this divide are two different ways of understanding how God works in history. The first could be called Providential Preservation. It holds that God not only inspired Scripture but also safeguarded its transmission through the Church. The text that the faithful used and trusted over centuries, therefore, bears the mark of divine oversight. Even as scribes copied by hand and translators rendered new editions, the guiding Spirit ensured that the essential Word was never lost.

The second view, Historical Recovery, arose with the rise of modern textual criticism. It seeks to reconstruct the earliest form of Scripture by comparing ancient manuscripts, analyzing linguistic patterns, and tracing scribal habits. Its underlying faith is that truth lies closest to the source, in the oldest and most original writings. If the Textus Receptus reflects the text as it survived, the Critical Text aims to reveal the text as it began.

These two approaches reflect different ways of trusting God. One believes in the Spirit’s work within the flow of time, sanctifying tradition. The other believes in the Spirit’s illumination through discovery, revealing what had been obscured. The first sees the Church as the ark of preservation. The second sees the scholar as the instrument of restoration. Both claim fidelity to divine truth, yet they follow distinct paths toward it.

For the believer who holds the longer verses and phrases dear, the difference is not academic but existential. The question is not whether each line was in the earliest autograph, but whether the God who guided those first writers could also have guided the centuries of worship that followed. To believe in providential preservation is to see history itself as a sacred vessel through which revelation continues to live.

The Draft Hypothesis: When Older May Not Mean Truer

Here lies one of the most compelling questions. What if the older manuscripts are not purer, but simply earlier drafts? In all literature, an author’s first version rarely represents the final form. Writers revise, clarify, and refine their work before it becomes authoritative. Even in the modern age, the latest edition of a book is usually considered the most reliable, not the earliest copy. If so, why should Scripture be different?

The earliest biblical manuscripts were produced in a world of oral teaching, community copying, and evolving liturgical practice. The apostles preached before they wrote, and their words were passed down, translated, and annotated. It is entirely possible that some early copies preserved unfinished or provisional forms of texts that later reached maturity within the Church’s collective memory. What scholars call “later additions” could just as easily be the Church’s final affirmations of what was true all along.

Textual critics acknowledge this possibility but manage it through rules of probability. They examine internal evidence, comparing style and vocabulary to decide what fits the author’s voice. They weigh external evidence, preferring manuscripts that are older and geographically diverse. Yet these are human judgments based on statistical likelihoods, not theological insight. They reconstruct a hypothetical “original” that no single community ever held in its hands.

From a theological perspective, it may be wiser to see revelation not as a single moment frozen in the past but as a living process. The Word matured as faith matured. The “later” text, shaped by prayer and use, could reflect not corruption but completion. In that sense, the Textus Receptus represents not the first stage of inspiration but its full flowering in history. The question then shifts from archaeology to providence, from what was earliest to what was most faithfully received.

The Spirit in Transmission

Scripture has always lived through the hands and voices of people. Before it was written, it was spoken. Before it was printed, it was memorized and sung. Each act of transmission was itself a form of devotion. The scribe copying the Psalms in candlelight, the monk chanting from memory, the mother teaching her child to pray; all became vessels of the same Spirit who first inspired the text.

To see this process as merely human error and repetition is to miss its sacred dimension. The preservation of Scripture was never just mechanical but communal. The Textus Receptus, in this light, is not a historical accident but the visible fruit of countless acts of faith. It reflects not only words on parchment but the prayers, confessions, and hopes of those who lived by them.

Modern textual criticism, for all its brilliance, often treats manuscripts as archaeological layers rather than living voices. It dissects the text with precision, yet sometimes forgets that these words were breathed in worship long before they were catalogued in libraries. The believer who reads a traditional translation encounters not only the text but also the echo of centuries. That resonance carries a spiritual authority no parchment age can measure.

Why Modern Translations Still Appeal

And yet, millions of Christians read and love modern translations. Their reasons are not shallow. Many see in them a sincere desire to honor Scripture’s original form. The use of older manuscripts is viewed as a sign of intellectual honesty, an effort to draw closer to what the apostles first wrote. For these readers, faith does not fear evidence. It welcomes discovery as another way God reveals His truth.

Others value modern translations for their clarity and accessibility. The ancient beauty of the King James Version moves the heart, but its language can be distant to modern ears. Contemporary versions open the Bible to those who might otherwise find it inaccessible. For pastors, teachers, and missionaries, the goal is to communicate the gospel effectively, and modern translations often serve that purpose well.

There are also those who trust the process itself. The methods of textual criticism, with their cross-referenced manuscripts and transparent footnotes, embody a kind of scholarly humility. They acknowledge uncertainty rather than conceal it. For readers formed by the rational spirit of the modern age, this openness to evidence and revision feels intellectually honest and spiritually responsible.

Finally, some churches maintain both traditions side by side. They read the critical text in study but pray the received text in worship. This quiet coexistence may reflect an unspoken intuition: that the Word of God cannot be confined to a single method of preservation. It survives both through discovery and through devotion.

The Two Faces of Faith

The debate between the Textus Receptus and the Critical Text is often framed as conflict, yet it can also be seen as the meeting of two kinds of faith. One believes that God’s guidance is visible in the steady continuity of history. The other believes that God’s light breaks through in moments of rediscovery. One trusts the collective witness of tradition; the other trusts the courage of inquiry.

Neither view negates the other. The faith of the scholar and the faith of the saint may belong to the same divine economy. The Spirit that preserved the text through centuries of copying may also be the Spirit that leads researchers to ancient manuscripts in forgotten deserts. Perhaps God allows both so that His people never grow proud in either certainty or ignorance.

What matters is not choosing sides but discerning the spiritual meaning behind the methods. Preservation reminds us that God works through faithfulness, through generations of believers who kept the Word alive. Recovery reminds us that God works through renewal, calling us to humility before the vastness of history. Together they form a paradox that mirrors the Gospel itself; ancient yet ever new.

The Word That Lives Beyond Text

At the end of the debate, Scripture itself invites a different kind of reverence. The Word of God has never been a static text but a living presence. It speaks when it is read aloud, when it is prayed in solitude, when it is sung in the company of believers. Whether one holds a Bible translated from the Textus Receptus or from the Critical Text, the same divine voice calls through the pages.

The doxology at the end of the Lord’s Prayer is a perfect image of this mystery. It may or may not have stood in the earliest manuscript, but it has certainly lived in the hearts of countless believers. When it is spoken, it becomes more than text; it becomes the Church’s breath of praise. Even if modern editions leave it aside, no believer who prays those words can doubt their truth. The glory and power remain God’s forever.

Perhaps God allows these differences to teach humility. The Scriptures have always contained within them the story of their own becoming; a history shaped by faith, error, discovery, and devotion. The divine Word, after all, is not only what was once written, but what continues to speak. The page may change, but the voice remains.

Whether we speak of preservation or recovery, of ancient parchment or printed page, the miracle is the same. The Word has survived. It has crossed centuries, languages, and controversies. It has endured not because of perfect manuscripts, but because of perfect grace. And every time it is read or whispered or sung, it lives again in the hearts of those who believe.

Image by Robert C