Artificial intelligence has already changed how we think about work, creativity, and problem solving. The leap we saw with generative models was not simply about smarter algorithms but about timing. By the time transformers arrived, the world had already built an immense library of text, images, and video. All of that material sat waiting to be transformed into patterns, predictions, and creativity. Without this abundance, the architecture itself might have stayed hidden in academic papers. Technology moves forward only when the world around it is ready.

This context is what made the leap so dramatic. When we think of GPT models or image generators, we see them as intelligent or even surprising. In reality, they are mirrors, reflecting patterns that were already everywhere. The internet became the raw clay. The power of these models came from absorbing countless books, articles, codebases, and conversations. Without such a foundation, they would have been impressive prototypes but not cultural events.

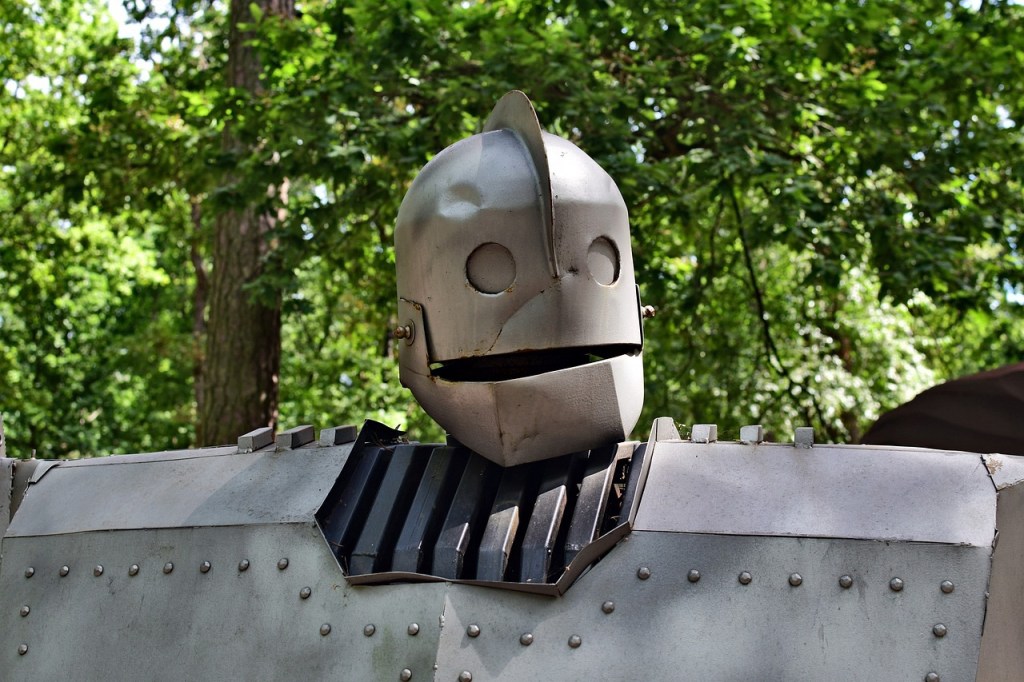

Physical AI is different. It points to a future where intelligence leaves the screen and enters the physical world. Robotics, motion planning, embodied perception, and dexterous manipulation are the pieces. They are what turn code into motion. But unlike words or pictures, there is no endless pile of data waiting to be mined. We are standing at the same edge, but the landscape looks less crowded.

The Problem of Scarcity

The challenge with physical AI is scarcity. A robot cannot learn to move naturally by reading about walking. It must feel forces, balance, friction, weight, and failure. These sensations are hard to collect at scale. Each attempt costs time, materials, and money. The world is not full of millions of sensors streaming motion data into public datasets. What exists is fragmented, proprietary, or experimental.

This scarcity changes everything. The internet allowed language models to grow almost passively. The world produced text naturally because humans were already writing. But few people are creating fine-grained motion data in the same way. Think of a caregiver lifting an elderly patient or a chef slicing fish. Every motion is full of micro-adjustments that no single dataset captures. Even if you filmed it, the data is visual, not kinesthetic.

To overcome this, robotics has turned inward. Since reality is expensive, researchers create digital twins of it. They build physics engines where gravity, weight, and collisions behave like the real world. They let robots live thousands of lifetimes in compressed time. These simulations are not perfect, but they allow an AI to fail millions of times without breaking a leg or burning a circuit. The problem is transferring those skills to real hardware. The simulation-to-reality gap is a mountain that many teams are still climbing.

Simulated Lives and Time Warps

Digital simulation is where physical AI currently breathes. What nature does in years, engineers now compress into hours. A robotic dog may “walk” through millions of steps in a lab computer before it ever takes one in the real world. It learns balance, speed, and recovery by falling, adjusting, and trying again, all in silicon. The principle is clear: the more you can practice, the better you become. Since practice in the real world is slow and costly, practice in the digital world becomes essential.

Yet simulation is not enough. The world is messy. Surfaces are not always even, objects are irregular, and sensors sometimes lie. A robot trained in a neat simulation often trips on reality’s cracks. This is why the research focus now is on making simulations more truthful and more diverse. They add randomness to surfaces, noise to sensors, and unpredictability to objects. They teach robots to be flexible, not perfect.

What you saw at robotics conventions is the fruit of this strategy. Many machines move with grace that would have been unimaginable years ago. They are agile, adaptive, sometimes even graceful. But watch closely and you see the difference. A living dog adjusts with a fluidity that no algorithm can fully match yet. The dream is there, but it is still early. If generative AI is at the stage of writing coherent essays, physical AI is still learning to form sentences with its legs.

Early Signs of Movement

The path, however, is accelerating. Sensors are cheaper, processors faster, and algorithms more sophisticated. Companies are sharing datasets that once were closely guarded. Wearable devices collect movement data from athletes, workers, and even pets. Motion capture studios that once served film and games now contribute to robotics. Every bit of this is feeding the future.

Competitions and public demonstrations show how close we are. Watching a humanoid robot run a short course or lift a box is no longer science fiction. These movements are still somewhat mechanical, but they hint at what is coming. Each new actuator, each lighter material, each clever control system closes the gap. The naturalness we seek is not far-fetched. It is just waiting for enough pieces to align.

The parallel to early generative models is striking. People once laughed at the clumsy sentences of early chatbots. They now write reports, code, and poetry. Movement will have its own timeline. When a robot opens a door as smoothly as a person, it will seem sudden. But behind that moment will be millions of quiet simulations, failures, and revisions.

From Cognitive Work to Embodied Labor

It is worth remembering that machines first displaced physical labor. Factories automated weaving, lifting, and shaping long before they automated thought. Steam, steel, and electricity turned physical effort into mechanical systems. The second wave, which we are living now, is about cognition. Computers and AI are replacing or augmenting work once considered purely intellectual. Writing, programming, diagnosing, analyzing, and even composing music are now shared with machines.

Physical AI may be the bridge between these two eras. It does not only think; it moves. It does not just respond; it interacts. This change will affect jobs that many thought safe. Caregivers, nurses, chefs, drivers, builders, cleaners. These are human roles rooted in movement, perception, and adaptation. Once robots can do them well enough, the economic conversation changes.

This does not mean humans vanish from the workplace. It means our role shifts again. Just as industrialization created new kinds of human work, physical AI will create its own demands. Maintenance, design, ethics, oversight, and creative applications will become more important. The frontier of work will move from muscle to mind, and then from mind to something like orchestration.

The Second Mechanization Wave

When that shift comes, it may feel familiar. We have seen mechanization before, but the difference now is intelligence. The first machines replaced strength. The next will replace coordination and skill. A caregiver’s touch, a carpenter’s judgment, a delivery worker’s pathfinding. These are complex but not mystical. They are patterns waiting to be learned, and machines are patient learners.

Industries will adapt unevenly. Hospitals may adopt assistance robots faster than restaurants adopt robotic chefs. Warehouses may become almost fully automated before nursing homes do. But each success will pull the next forward. Cost, safety, trust, and regulation will guide the pace, but the direction is set.

There will also be pushback. Some will fear the loss of human contact in care. Others will question safety or ethics. These are important debates, and they must be faced. A robot lifting an injured person must be trusted not only to be strong but to be gentle. This is not only an engineering problem but a human one. We will need to decide how much of ourselves we want to share with machines.

The Road Ahead

The bottleneck is data. Motion must be recorded, shared, and refined. This means more wearables, more motion-capture archives, more studies of animals and humans. It means sensors that capture not just position but force, temperature, vibration, and context. The robot of the future will need a memory not of words but of movements.

Hardware will meet software. The brain of a robot will be trained with the body in mind. Actuators will be designed for the learning algorithms that drive them, not as afterthoughts. Materials will flex and adapt like muscles. Cameras and sensors will be placed not where convenient but where perception demands. This merging of fields will be one of the most exciting aspects of physical AI.

And with it will come questions. How do we secure machines that move? How do we prevent harm when power and autonomy meet? How do we balance efficiency with dignity when a robot feeds a patient or delivers care? These questions are not distractions. They are part of the work. Physical AI will not only challenge engineering; it will challenge culture.

A Future That Moves Naturally

If history is a guide, the moment of surprise will arrive quietly. One day a video will surface of a machine walking, lifting, or even playing in a way that feels alive. We will see it not as a trick but as a natural step. At that moment, the years of scarcity, simulation, and struggle will feel like a distant memory.

The leap will not erase humans. It will remind us that intelligence is not only about thought. It is also about movement, grace, and response. Physical AI will not take away the value of care, skill, or craft. It will simply change how they are expressed. Machines will join us in the physical world, and that will force us to ask again what makes something truly alive.

The next wave of innovation will not be silent. It will walk, lift, serve, and perhaps surprise. Just as the transformer moment changed our screens, the physical AI moment will change our streets, homes, and workplaces. The question is not whether it will come but when. And when it does, it may feel less like a leap and more like something inevitable, a rhythm we had been moving toward all along.

Image by Piotr Zakrzewski