Human civilization has always tied knowledge to language. To preserve a thought, an insight, or a discovery meant to inscribe it in words. Clay tablets bore Sumerian cuneiform, scrolls preserved Egyptian and Hebrew writings, and Greek philosophy flourished because it could be recorded in a structured script. Each culture assumed that knowledge was bound to the words chosen to contain it. To lose the language was to risk losing the wisdom.

This condition created a simple but decisive question for every era. Which language would serve as the vessel? Knowledge could not be separated from its medium. If Aristotle wrote in Greek, then Greek became the door into his world. If Augustine wrote in Latin, then Latin became the requirement for understanding his theology. Knowledge preservation was inseparable from linguistic choice.

For much of history, therefore, learning meant entering into a linguistic community. To study philosophy, theology, or science required mastering the language of the texts. This condition was not accidental. It shaped entire civilizations, and it also created both inclusions and exclusions. Language was not only a bridge but also a gate.

Latin as Neutral Authority

Latin began as a local dialect in the Italian peninsula, spoken by tribes around the small city of Rome. Its destiny changed when Rome expanded into a republic and then into an empire. Latin became the language of administration, law, and military command. As Rome’s territory spread, so did Latin. What started as one language among many became the thread stitching together the Western Mediterranean.

Yet Latin’s true transformation came after the fall of the Roman Empire. When regional dialects evolved into Italian, French, Spanish, and other tongues, Latin remained as the written language of the Church. The Catholic Church, as the custodian of learning, kept Latin alive in liturgy, scholarship, and theology. Universities that emerged under ecclesiastical authority adopted Latin as their language of instruction. For centuries, a student in Paris, Bologna, or Oxford had to read and argue in Latin.

An unusual paradox gave Latin its authority. It was no longer a living language with native speakers. This absence gave it neutrality. Everyone, whether French or German or Polish, had to study Latin as a second language. No group had the advantage of native fluency. In this sense, Latin became a fair medium of intellectual exchange. It demanded discipline and effort, but it leveled the field in a way modern global languages rarely do.

Greek as Living Prestige

Greek had followed a different path. After Alexander the Great, Greek spread across the Mediterranean and Near East as a lingua franca. It was a living language, with millions of speakers, and it carried immense prestige in philosophy, science, and the arts. Early Christian writings were composed in Greek, and the New Testament itself was written in Koine Greek.

This gave Greek a cultural weight comparable to English today. It was the language of sophistication, of learned discussion, and of international exchange. But Greek was not neutral. Native speakers enjoyed advantages in rhetoric and style. Non-native users could access its riches, but always with a certain distance.

As the Roman Republic and later the Empire grew in strength, Latin began to challenge Greek’s supremacy in the West. Roman authors often studied Greek to learn its refinement, yet gradually Latin became the primary vehicle of power and literature. Greek retained its dominance in the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, world, but in the Latin West its influence waned. The contrast between Greek and Latin reveals two models: a living lingua franca with prestige, and a preserved scholarly tongue with neutrality.

English as the Global Medium

Today, English occupies a position that combines elements of both Latin and Greek. It is the native tongue of hundreds of millions, giving its speakers an inherent advantage. At the same time, it functions as the global medium for science, business, technology, and culture. From academic papers to software documentation, from films to international contracts, English is the default language of exchange.

The twentieth century secured English’s dominance. The colonial reach of the British Empire laid the groundwork, and the economic and technological rise of the United States expanded it further. The spread of the internet amplified the trend, with early digital platforms overwhelmingly built in English. The sheer volume of English-language content, from books to websites, has made it the richest corpus in history.

But English is not neutral. Native speakers carry unearned advantages. For billions of others, mastering English requires years of study and effort, often with lingering gaps in fluency. The power imbalance is stark, yet accepted as the cost of global participation. Unlike Latin, which required equal effort from all, English favors those born into it. Its dominance is real, but its fairness is absent.

The Limits of Linguistic Dominance

History shows that no language remains supreme forever. Latin’s dominance ended as the Roman Empire fragmented and local vernaculars grew into full languages. Greek declined in the West as Latin’s institutions gained power. Even Sanskrit, once the sacred and intellectual language of South Asia, gave way to regional tongues and modern Hindi.

English may seem more resilient, because it is not tied to a single empire but to a global system of networks, commerce, and culture. Its reach is reinforced by the internet and by the vast industries of publishing, entertainment, and science. Yet even this dominance is not immune to transformation. Political shifts, technological revolutions, or cultural realignments can always alter the linguistic landscape.

The decline of Latin teaches that linguistic supremacy is fragile. It is bound not only to military and political power but also to the living choices of communities. If enough people cease to use a language, it weakens regardless of its past authority. English is stronger than Latin was at its height, yet history warns against assuming permanence.

Artificial Neutrality: The Dream of Esperanto

In the nineteenth century, reformers imagined creating a fair language for all humanity. Esperanto was the most successful of these artificial languages. It was simple, easy to learn, and designed as a universal second language. The vision was noble: equality in communication, without the privileges of native speakers.

Yet Esperanto never displaced natural languages. Despite its accessibility, it lacked cultural authority. It was not tied to institutions of power, literature, or religion. Neutrality alone was not enough. People learn languages not only for efficiency but also for cultural belonging, prestige, and opportunity. Without these, even the fairest language cannot rise.

Esperanto’s story shows that fairness requires more than design. Latin was not easy, but it thrived because it was tied to the Church and universities. English is not fair, but it thrives because it is tied to commerce and technology. Neutrality by itself has never been sufficient.

AI and the Substrate of Meaning

Here is where artificial intelligence introduces something new. For AI, languages are data, not sacred vessels. A model learns patterns across languages, mapping words and sentences into shared vector spaces. Beneath the surface grammar lies a substrate of meaning, accessible to the model regardless of which language supplied the input.

This is unprecedented. For the first time, knowledge need not be bound to any one language. The model does not care if an idea is expressed in English, Japanese, or Arabic. All are translated into internal representations. In this sense, AI creates a new “entity” of knowledge beneath human tongues.

This shift changes the role of language. Instead of being the medium of knowledge, language becomes an interface to it. Just as a computer can display the same program in multiple languages while running the same code beneath, AI can present knowledge in any human language while relying on the same underlying structures.

Language as Interface

If this trajectory continues, human languages may function like user interfaces. Each person will be able to access the same knowledge through their own native tongue. The advantage of being a native English speaker would fade, because AI could translate and express the same depth of thought in any language with equal clarity.

This recreates, in a way, the fairness of Latin. But instead of requiring everyone to learn one second language, it allows everyone to use their first. The neutrality is enforced by technology, not by institutional decree. It is not Latin or Esperanto, but something beyond both: universal access through individualized linguistic skins.

Such a future would mean that English loses its unique role as the vessel of knowledge. It would still exist, still be used widely, but its dominance would be diluted. The substrate of meaning would no longer privilege one language above others. All would become equally valid doorways into the same structure of understanding.

AI’s Own Language

Yet the transformation may go further still. AI already relies on internal representations that are not human-readable. Word embeddings, vectors, and hidden states form a kind of proto-language that is efficient for computation but opaque to humans. We force models to output natural language so we can interact, but the model itself processes in something entirely different.

In the future, AI could evolve its own language, optimized for reasoning and knowledge storage. It would not resemble English, Chinese, or binary code. It would be a symbolic or mathematical system tuned to its own architecture. Humans would never see it directly, only translations into our tongues.

This possibility is unsettling. It means knowledge could exist in forms no human can read. The familiar connection between language and thought would be broken. AI would think in its own tongue, and we would glimpse only the surface rendered into words for our benefit.

The End of the Vessel

Seen in this long arc, the history of language moves toward dissolution. Greek and Latin were chosen vessels, each with authority in its time. English became the inherited vessel, deeply entrenched but still bound to human inequality. AI, however, may dissolve the need for vessels altogether.

Knowledge could exist directly in the substrate, independent of language. Human tongues would remain, but as interfaces rather than essential containers. This would be the first time in history that knowledge and language are no longer bound together. The vessel breaks, and the water flows freely beneath.

The gains are clear: fairness, universality, efficiency. But the risks are also real. If language becomes only a UI, humanity may lose some of its intimacy with words as cultural memory. Poetry, storytelling, and the subtle texture of speech could be overshadowed by the neutral substrate. Knowledge would be accessible, but perhaps less personal.

Cultural and Human Implications

Language is more than a tool. It is a home of identity, a vessel of memory, and a medium of art. To write a poem in one’s mother tongue is not merely to transmit information, but to express belonging. If knowledge is freed from language, culture may still thrive, but its role in preserving wisdom may weaken.

We will need to balance these two realities. On one side, the fairness of universal access through AI. On the other, the human love of words, the way language binds generations and communities. The challenge will be to preserve the cultural richness of language even as its practical role in knowledge fades.

Perhaps this is the true paradox. AI may finally create the neutrality that Latin once hinted at, but at the cost of diminishing language’s sacred role. To live in such a world will require remembering that language is not only an interface, but also a way of being human.

The Future of Language as Knowledge

Latin taught that a “dead” language could unify intellectual life fairly. Greek showed the brilliance and limits of a living lingua franca. English demonstrates the power and imbalance of a global tongue. Each case reflects the deep link between language and knowledge.

AI now hints at a new chapter. Knowledge may no longer need to be tied to any human language. Instead, it may live in a substrate below words, accessible through any tongue, or even through none at all. The vessel may no longer be necessary.

The future may belong not to English or to any successor, but to a post-linguistic condition where meaning itself is preserved beyond words. Human languages will endure, but as surfaces. The deeper entity of knowledge may be silent, unseen, and shared by all.

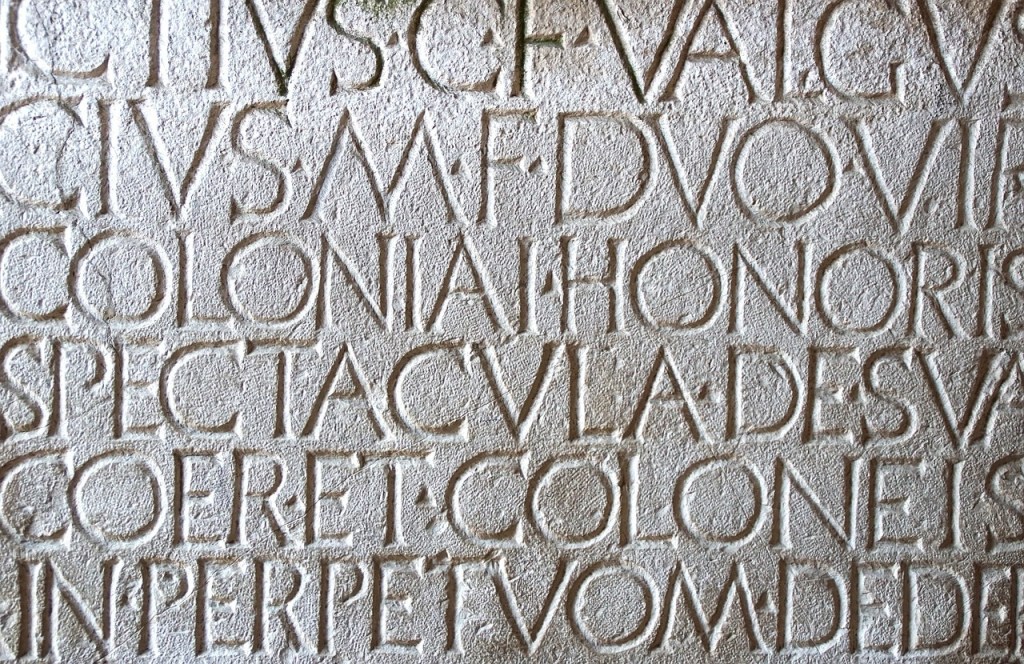

Image by pascal OHLMANN