The relationship between plain text and markdown is often taken for granted. Many assume they belong to the same family, that a preference for one naturally includes the other. But is that really true? When I move between a pure plain text editor like Notepad or TextEdit and a markdown editor like Typora or Obsidian, I feel a subtle difference that is more than technical.

Plain text is often celebrated as the purest form of digital writing. Markdown is presented as its natural extension. Yet the more I write, the more I sense that the spirit of each is not identical. Plain text holds to an uncompromising minimalism. Markdown, however light, already introduces structure, and with that structure comes complexity.

The distinction may seem trivial, but it reveals something deeper about how we imagine freedom in writing.

The Spirit of Plain Text

Plain text is the digital equivalent of ink on paper. There is nothing beyond the letters themselves. No formatting, no hidden instructions, no invisible metadata shaping how it looks. What you see is what you get, and what you type is exactly what is stored.

This is why plain text has survived for decades. From the earliest computer terminals to today’s simplest editors, the format remains unchanged. It is universal, portable, and timeless. You can open a plain text file written thirty years ago and it will appear the same today.

But the appeal is not only technical. The emotional attraction lies in its purity. A blank window in Notepad or TextEdit resembles silence before music. It invites you to fill it with words, and nothing distracts you from that act. No preview, no toolbar, no formatting icons. Just letters on a screen.

For some, this is the ultimate freedom. The absence of features is the feature. The lack of options is not a limitation but a liberation.

The Promise of Markdown

Markdown emerged in the early 2000s as an attempt to solve a practical problem. Bloggers and programmers wanted a way to write content that could be easily converted to HTML without staring at endless tags. John Gruber and Aaron Swartz created markdown with the idea that plain text should remain human-readable while also carrying formatting instructions for machines.

The beauty of markdown is in its balance. A header is just a # before a line. Italics are wrapped in single asterisks, bold in doubles. Links are written as [name] and (url) and still readable in raw form. You can open a markdown file and understand it without any special software.

This is why markdown became beloved in technical communities. It promised simplicity without sacrificing structure. It gave writers a tool that could travel between the rawness of plain text and the polish of HTML or PDF. It made writing both readable and publishable.

In this sense, markdown is not a betrayal of plain text but a compromise. It does not abandon minimalism, but it shifts the meaning of minimalism toward usability.

The Complication of Editors

If markdown were only syntax, the debate might end there. But tools shape our experience as much as syntax does. And this is where markdown editors complicate the story.

Many markdown applications adopt a dual-view model: one pane for the raw text, the other for the formatted preview. At first glance this seems convenient. You can see both your words and their final form. But to lovers of plain text, it feels like an intrusion. The second pane, however helpful, doubles the environment. It turns a silent page into a dashboard.

Even single-pane editors like Typora, which render markdown as styled text while you type, introduce a subtle tension. The simplicity is polished but not pure. The tool is mediating your text in real time, hiding the syntax as if it were something to be embarrassed by. You are no longer looking at the file itself, but at its continuous transformation.

This is where markdown reveals its cultural origins. It was designed by programmers, for programmers. The dual-view, the hidden syntax, the export features all carry the flavor of engineering culture. They value transformation, not stasis. For them, the text is always on its way to becoming something else.

But for those who cherish plain text, that is exactly the problem. The text should not be on its way anywhere. It should already be complete in itself.

Freedom vs Framework

At the heart of this divide is the meaning of freedom. Plain text offers freedom from all imposed frameworks. There is nothing between you and your words. Markdown offers freedom through a framework. By adopting a light syntax, you gain the ability to move your text across platforms and formats.

Some find this liberating. Markdown makes text portable, shareable, publishable. Others find it constraining. The very presence of syntax means the file is not just words anymore. It is words bound to a system.

This is why plain text and markdown, though close, are not the same. Plain text is silence. Markdown is minimal music. Both are simple, but their simplicity is different in kind.

Cultural Perceptions

Writers, programmers, and minimalists each perceive this divide differently.

For programmers, markdown feels like natural language. They are already accustomed to syntax, tags, and markup. Markdown is elegant because it reduces clutter while remaining functional. The dual-pane editor is not an intrusion but a reassurance.

For writers who seek purity, markdown feels like an intrusion. The presence of # and * interrupts the flow of language. It is no longer just prose, but prose peppered with signals. The dual-pane editor feels like clutter. Even Typora’s smoothness feels artificial, like a mask hiding the reality of the file.

For minimalists, plain text represents a deeper ideal. It is not just about writing but about resisting the bloat of software culture. Every toolbar, every hidden layer is seen as noise. For them, plain text is not only a tool but a statement: less is enough.

AI and the Question of Structure

A new perspective arises when we consider artificial intelligence. Many people today claim that markdown is the most compatible format for generative AI. The reasoning is clear. Markdown preserves a minimal level of structure. Headings, bullet points, and simple tags give shape to content without burying it in complexity. Compared to binary formats like Word or PowerPoint, markdown is light, portable, and easy to parse.

In contrast, plain text is often seen as too bare. It contains nothing but the sequence of words. Without headings or markers, the file does not reveal which sentences form a section, which lines are a list, or which words carry emphasis. From a technical point of view, markdown seems superior because it makes structure explicit.

Yet this view may be shortsighted. Generative AI does not operate like older software that depended heavily on syntax. A model does not “read” the markup to grasp meaning. It infers meaning through semantics. It looks at the content, not the tags. When AI summarizes an article, it is not merely tracking # or *. It is understanding sentences in relation to each other. It is reconstructing the hidden structure from the flow of words.

This is why AI can summarize plain text with remarkable accuracy, even when no structural markers are present. It is also why AI can handle binary documents, stripping away formatting and extracting meaning from raw sentences. The work of AI lies in semantics, not syntax.

From this perspective, plain text gains a surprising advantage. By remaining bare, it resists the temptation to outsource meaning to syntax. It keeps us in the purely semantic domain of letters and sentences, the same domain where AI excels. In a sense, plain text trusts both the reader and the machine to recover structure from meaning itself. Markdown, by contrast, risks treating structure as something to be imposed rather than discovered.

The irony is striking. While people celebrate markdown as the most AI-friendly format, plain text might be closer to the spirit of AI’s actual intelligence. AI thrives in the space where meaning is implicit, where order is not prescribed but interpreted. Plain text embodies that same principle. It is not structure that guarantees understanding but the deeper web of relations among words.

The Philosophy of Tools

The difference between plain text and markdown reveals a broader truth. Tools are not neutral. They embody philosophies. Plain text embodies the philosophy of purity. Markdown embodies the philosophy of portability. One is about being, the other about becoming.

This is why debates about editors can feel so intense. They are not only about features but about values. When someone insists on using Vim or Notepad, they are not just choosing convenience. They are choosing a worldview where text should remain unmediated. When someone chooses markdown, they are choosing a worldview where text should be structured for movement.

The choice is less about what you write and more about how you want your words to live.

Between Silence and Music

Perhaps the best way to think of plain text and markdown is through metaphor. Plain text is silence. It is the absence of adornment, the calm background against which words stand out. Markdown is minimal music. It introduces rhythm, markers, and structure without overwhelming the melody.

Neither is superior. Each serves a different temperament. Some writers thrive in silence, others need rhythm. Some want their words to remain unshaped, others want them prepared for transformation.

The mistake is to assume that those who love plain text must also love markdown. The relationship is closer to siblings than to identical twins. They share a lineage but not a destiny.

The Choice of Freedom

The debate is not really about text files. It is about our relationship to freedom, structure, and meaning. Plain text represents the dream of absolute freedom: words without frameworks, expression without mediation. Markdown represents the dream of functional freedom: words that move easily across systems while retaining their human readability.

Both are beautiful in their own way. But they answer different desires. One seeks peace, the other seeks movement. One is content with silence, the other hums with minimal music.

With the rise of AI, the contrast becomes even more revealing. AI does not need syntax to grasp meaning. It reconstructs order from semantics, the very space where plain text lives. This does not make markdown irrelevant, but it shows that the value of structure may lie less in helping machines and more in helping ourselves.

So perhaps the question is not whether plain text and markdown are the same, but which kind of freedom one values more. The freedom of silence, or the freedom of minimal music. The freedom of letting words be, or the freedom of preparing them for transformation. Both are paths worth walking, but they do not walk in the same direction.

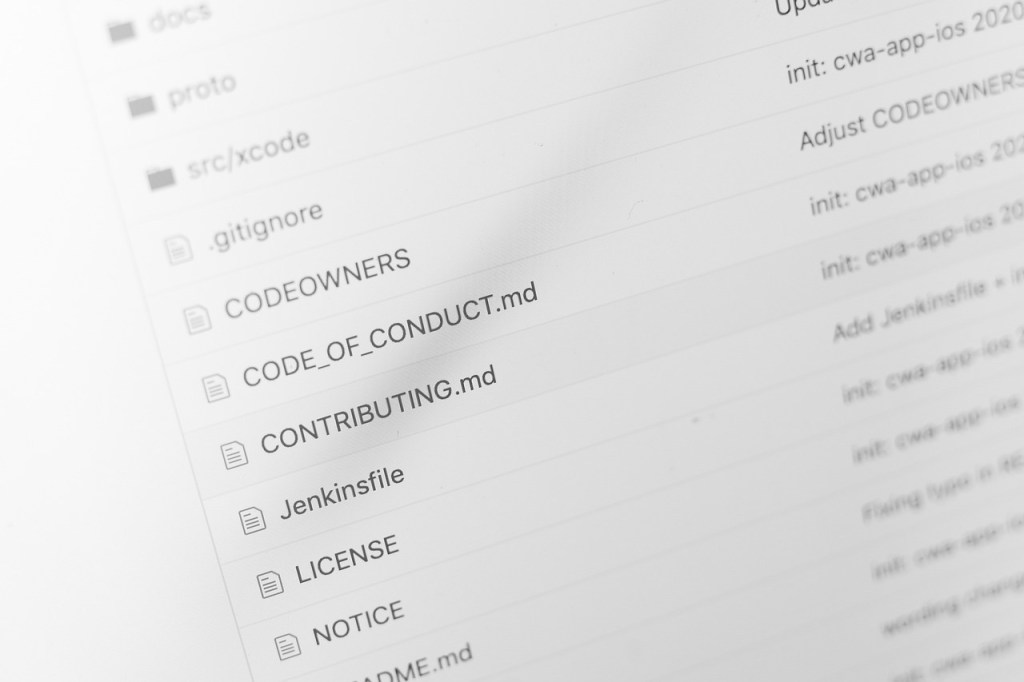

Image by Markus Winkler