In the summer of 2025, Denmark made headlines, not for its climate goals, social policies, or cultural exports, but for a quiet shift in its digital strategy. The Ministry of Digital Affairs announced that it would begin replacing Microsoft Windows and Office 365 with Linux and LibreOffice across its public sector infrastructure. For most people outside of tech circles, this might sound like a minor administrative change. But for those who have spent time thinking about the implications of software, data, and control, this decision felt significant.

This was not just about budget. Yes, Denmark cited soaring costs, with Microsoft licensing fees rising by 72 percent in just five years. But behind the numbers was a deeper concern: control. In an era where data is both asset and liability, the question of who owns the software that touches every part of a nation’s information infrastructure becomes more than technical; it becomes political.

Denmark’s move is part of a wider European trend toward digital sovereignty. The aim is not just to cut spending, but to reduce reliance on foreign tech giants. The logic is simple. If a country relies entirely on one company’s infrastructure for documents, communication, and cloud services, then it is not fully independent. And as we’ll see, this notion of dependence runs deeper than national borders. It reaches into our personal lives, our memories, and even our concept of permanence.

Comfort and Control

Many of us have experienced the seductive comfort of modern software ecosystems. OneDrive quietly syncs across devices. Your files are always accessible, your settings saved, your transitions between work and home seamless. But as these tools grow more integrated, they also become harder to leave. Try exporting years of notes from OneNote, or fully replicating the collaborative features of Microsoft Word in a plain text environment. What once felt like a convenience begins to resemble captivity.

This is where the metaphor of OneDrive as a kind of “soft ransomware” comes into play. It’s not malicious, and it’s certainly not illegal, but the dynamic is similar. Your data is stored, but not on your terms. You must pay, either in subscription fees or in brand loyalty, to keep it accessible and functioning. The more you integrate, the more you depend. And the more you depend, the harder it becomes to reclaim ownership.

To resist this, some turn to open formats. Markdown. Plain text. LibreOffice documents. These aren’t just preferences; they are acts of self-preservation. Choosing open tools is a way of refusing the slow drift toward dependency. It’s less about ideology and more about keeping the future open. The irony is that while open tools may be less polished, they offer something more valuable: the possibility of freedom.

The Illusion of Longevity

People often argue that open source formats are more durable. After all, you can still read a plain text file from the 1980s, whereas good luck opening an old Microsoft Works file today. The promise is longevity through simplicity. But even here, the picture is complicated.

When we think about data preservation, we often imagine that local storage, USBs, hard drives, DVDs, offers a kind of permanence that cloud services cannot. But this, too, is a comforting illusion. Many of us have stories of lost floppies, corrupted drives, or forgotten backups. In your youth, you may have carefully stored your writings on disks, confident they would last. Yet today, they’re gone. Not because of sabotage or theft, but because media dies, formats fade, and life moves on.

The cloud, in contrast, feels eternal. Google never forgets. Dropbox is always there. Files live in a kind of suspended animation, waiting for us to summon them. But that illusion depends on something fragile: the continuity of the service. What happens when the platform changes its terms, removes your storage, or shuts down entirely? Your data is safe, until it isn’t.

So we return to the central question: which is more permanent, local or cloud? Both seem secure until they aren’t. Each has risks, and neither offers a guarantee. Permanence, it turns out, is harder to define than it seems.

Stone, Paper, and Silicon

Digital data is fast, light, and infinitely replicable. But these very features make it fragile. To preserve it, we must keep copying it. Backup becomes a daily ritual, and redundancy is a necessity. Unlike stone or parchment, digital media requires constant maintenance. It does not age well on its own.

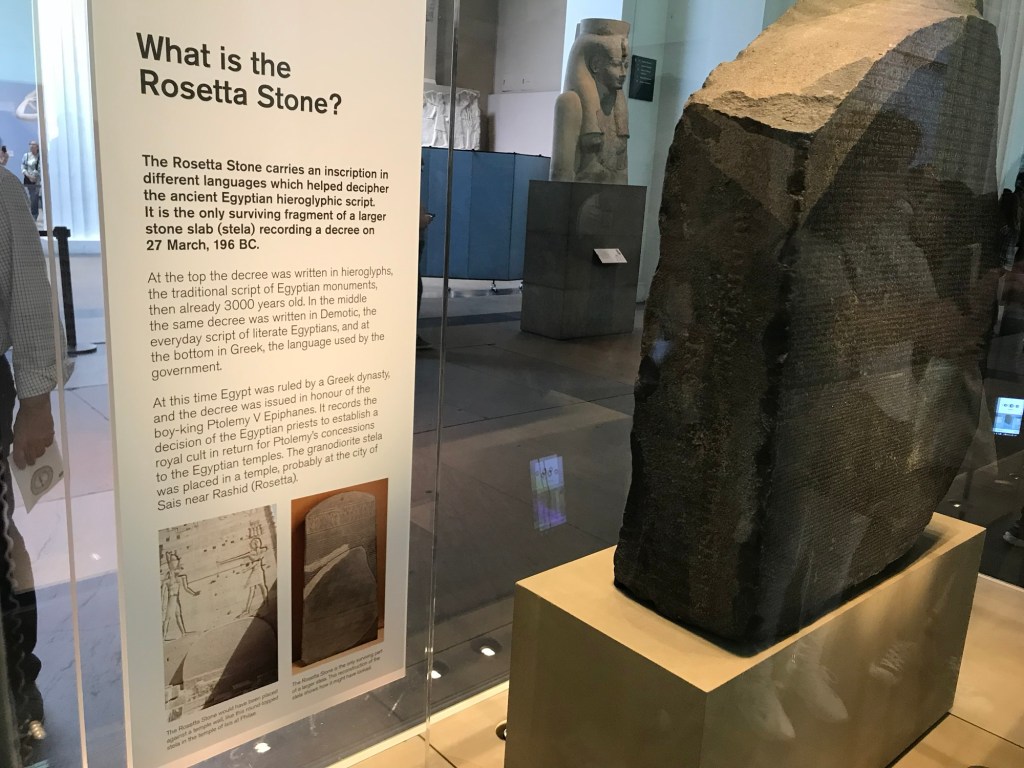

Compare this with the Rosetta Stone. Chiseled into granite over two millennia ago, it survived floods, wars, neglect, and empire. It sat, silent and intact, waiting to be found. Or think of the medieval manuscripts that endured centuries of humidity and candlelight. We still read them because their media was physical, tangible, resistant to entropy.

Now imagine a world where humanity vanishes tomorrow. In a thousand years, what would remain? Not our photos. Not our emails. Not our cloud storage. Even the servers would corrode, the power would fail, and the storage media would degrade. From the perspective of deep time, our civilization may leave behind fewer traces than a Mesopotamian city.

This is not a reason to abandon digital tools. But it is a reason to be cautious in trusting them with everything we value. Preservation is not just a matter of format. It is a matter of material reality.

The Cost of Abundance

Today we store more than any civilization in history. We record everything. Photos, messages, thoughts, memories; all saved, synced, and backed up. Yet this abundance comes with a strange anxiety. The more we save, the more we fear losing it.

Paradoxically, this fear leads us to trust the systems that are easiest to use, even if they are the least transparent. We hand over our data to platforms with the hope that they will outlast us. But in doing so, we create new dependencies. The act of saving becomes the act of surrendering.

In contrast, open tools demand more effort. Markdown files don’t sync themselves. Plain text has no built-in backup. But these formats give us something that cloud services cannot: awareness. When you manage your own files, you are reminded that permanence is not guaranteed. This discomfort can be a gift. It forces us to think, to organize, and to care.

In the end, data is not memory. Memory is what persists in meaning. And meaning cannot be preserved by storage alone. It must be cultivated through use, through attention, and through intentional practice.

Freedom, Risk, and the Weight of Choice

Every digital decision we make involves a trade-off. Use a platform, and you gain features. Avoid it, and you retain autonomy. Trust the cloud, and you gain access. Store locally, and you gain control. But in every case, you also inherit the risks that come with that choice.

This is not a matter of right or wrong. It is a matter of values. Do you prioritize ease or endurance? Compatibility or independence? Security through centralization or security through simplicity? There is no universal answer.

What matters is that we are aware. That we ask the question. That we refuse to drift unconsciously into dependence simply because the interface is smooth or the font looks nice.

Denmark’s move away from Microsoft may seem like a footnote in the story of tech. But it is, in fact, a small reminder of a larger truth. Every platform, every tool, every system shapes not just how we work, but what we remember, how we preserve, and who we become.

Choosing What Lasts

We can’t preserve everything. Nor should we try. But we can be more thoughtful about what we entrust to the digital world. Not all memories belong in cloud drives. Not all notes must be stored forever. What we choose to preserve reflects what we care about. And how we preserve it reflects what we believe about time.

In this light, open formats are not relics of the past. They are seeds for a future where meaning is not held hostage by subscriptions or software updates. Plain text may lack polish, but it survives. Markdown may be simple, but it remains readable. These tools remind us that endurance often comes in unglamorous forms.

To write in stone is to seek permanence. To write in the cloud is to seek access. Each has a place. Each has a cost. And in between, we live, choosing what to forget and what to carry forward.

Image: A photo captured by the author