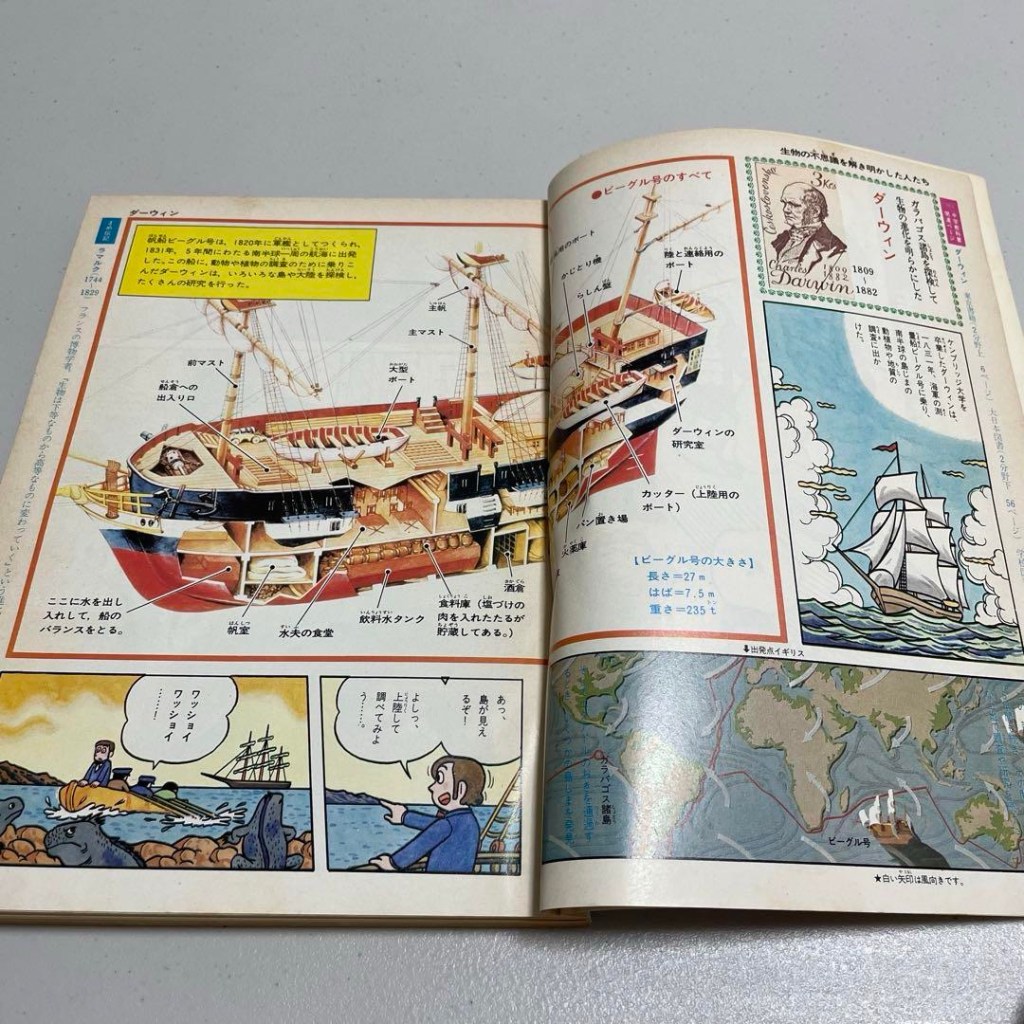

I recently stumbled upon some photos of an old science magazine I used to read as a child. It was one of those thick special issues of 6年の科学 (Science for Sixth Graders), a Japanese magazine for elementary school students. Though the original copy was long gone, just seeing the table of contents again brought everything back: the cartoon versions of great scientists like Newton, Curie, Darwin, Galileo, and Einstein.

I must have read that magazine countless times. I didn’t fully understand the science, of course. But the characters fascinated me. Their stories were drawn like short manga, each showing a moment of discovery, a problem solved, or a strange quirk in their personality. Looking at the pages now, I realize this was probably my first real encounter with these towering figures. Their names and faces quietly settled in my mind; long before I could spell “relativity” or knew what a hypothesis was.

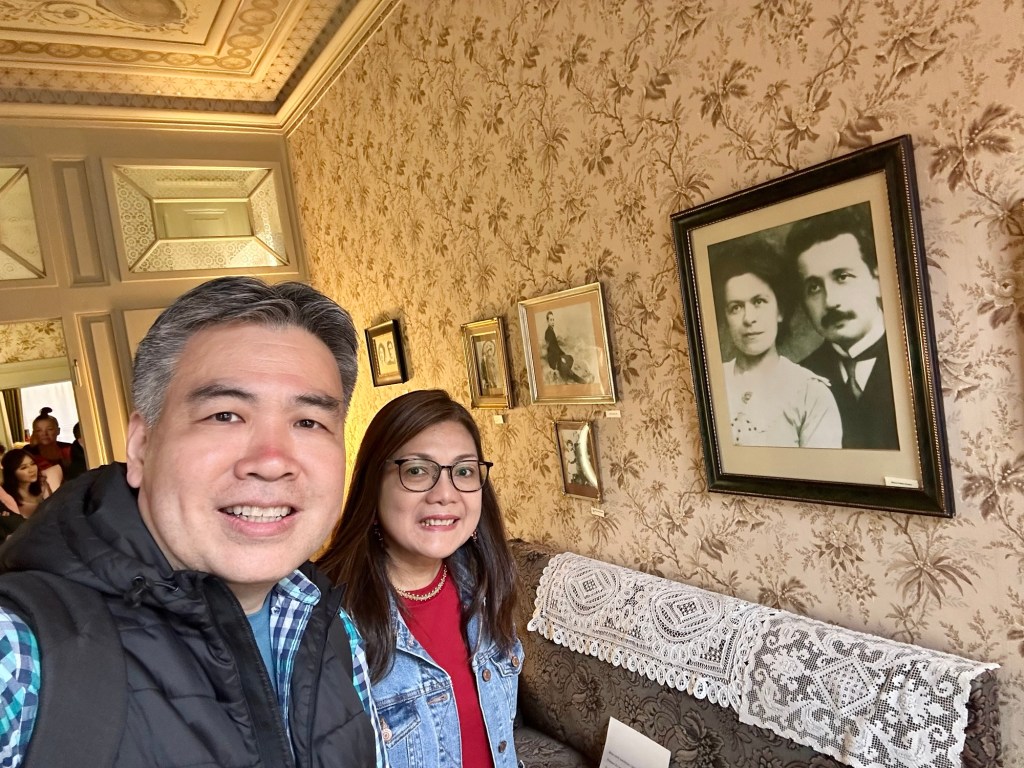

And then, decades later, I found myself in Bern, standing in the modest apartment where Einstein lived during his miracle year of 1905. That quiet visit, during our trip to Switzerland in September 2024, felt surprisingly emotional. I realized that one reason the moment meant so much wasn’t just because of Einstein’s genius. It was because I had carried his name with me since childhood. That name had once lived inside the pages of a children’s magazine, printed on paper made by people who believed that kids should grow up with curiosity, even in a world without the internet.

A Magazine from the Past

In the pre-digital age, the world reached us through paper. Books, newspapers, and monthly magazines were not just sources of information; they were gateways to wonder. Among the most beloved of those was Science for Sixth Graders, a Gakken-published magazine tailored to the curiosity of sixth graders. Every issue was filled with experiments, trivia, cross-section diagrams, and manga-like storytelling that brought abstract ideas down to a child’s level.

This particular special issue, which I recently rediscovered in photo form, was dedicated to the lives of famous scientists. And not just as a list of dates and achievements, but as stories with humor, emotion, and drama. It was crafted for children, but never talked down to them. It sparked something in me, though I wouldn’t have known to call it that at the time.

Even then, without fully understanding it, I loved reading those pages. They had a certain warmth. You could feel the effort that went into creating something both educational and delightful. I didn’t realize it then, but those stories were quietly preparing my mind to see the world as something worth asking questions about.

Meeting the Minds That Shaped the World

The table of contents from that issue is now, in hindsight, a roll call of lifelong companions. Many of the figures I first met there continued to appear throughout my academic journey, and later, in quiet moments of reflection. The magazine divided them into categories, each with its own narrative style.

First came the “Inventive Thinkers Who Made Discoveries”:

Archimedes, Pascal, Lavoisier, Jenner, Faraday, Darwin, Fleming, Edison, Curie, and Einstein. These were the problem-solvers, the tinkerers, the ones who got their hands dirty and changed how we live.

Then came those who “Changed the World with Ideas”:

Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes, Newton, Laplace, and Kant. These thinkers pushed the boundaries of reason and reshaped the way humans understand truth and logic.

Finally, there were the explorers of Earth and the cosmos:

Halley, Lamarck, Lyell, Haeckel, Hess, Wegener, Hubble, Gamow, and Hawking. Their stories stretched across time and space, from the origins of life to the distant stars.

As a child, I didn’t yet have a map of history or science. But I had this. I had these faces and names, presented not as unreachable figures but as humans, drawn with quirks, questions, and quiet triumphs. It’s easy to forget how powerfully early exposure works. We may not remember the facts, but we remember the tone, the faces, the feeling of being invited to care.

Einstein, Then and Now

Einstein was the one who stayed with me the longest. Maybe it was the way he was drawn in the magazine, with wild hair, a gentle smile, and a faraway look in his eyes. Or maybe it was because his name kept showing up throughout life, in classrooms, books, media, and even jokes. He became both a symbol and a mystery.

As I grew older, I learned the meaning of E=mc², and read about the miracle year in which he published papers that would change physics forever. I encountered him not just as a physicist, but as a thinker on philosophy, war, peace, and humanity. Still, somewhere in me remained that first image, childlike, earnest, and curious.

So when I walked through his former apartment in Bern, it wasn’t just a historical site. It was something far more personal. The rooms were simple. A table, a chair, a bookshelf. A quiet space in which one could imagine thought taking shape. And in that stillness, something within me also returned, something soft and young, like remembering the scent of a childhood room.

It was not just about Einstein. It was about the memory of meeting him for the first time, not as a scholar, but as a curious boy turning pages.

Gratitude Across Generations

Rediscovering that magazine made me realize how much I owe to the adults of that era. In a time when there were no online search engines or educational apps, people still found a way to bring the world closer to children. The editors, writers, and illustrators behind Science for Sixth Graders believed that kids could appreciate complexity when it was shared with warmth and imagination.

And just as important were the parents, our parents, who believed in the value of these materials. They bought the magazines, encouraged reading, and created a home where curiosity was welcomed. They trusted that knowledge, even when not immediately useful, was worth having.

I now see those choices as quiet acts of love and long-term thinking. They didn’t know where our interests would lead, but they gave us tools, exposure, and stories. And perhaps most importantly, they trusted that children could engage deeply with big ideas when given the right entry point.

In that sense, this magazine wasn’t just a publication; it was a legacy. A bridge from one generation to the next, built not by loud declarations but by small, consistent efforts.

Curiosity That Never Aged

As we left the Einstein House in Bern, I didn’t feel like I was stepping out of history. I felt like I had just revisited something inside myself. That quiet, steady love for knowledge that had started so long ago, not in a grand university or lecture hall, but in a corner of my childhood room, with a stack of magazines and an open heart.

Even now, I find that same curiosity shaping how I see the world. It’s not loud or urgent. It’s slow, reflective, and patient. And I believe it was made possible by moments that seemed small at the time, like reading about Einstein in manga form, or flipping past a diagram of the solar system.

The internet offers us information in overwhelming quantity. But something about those analog days, those crafted pages and thoughtful illustrations, left a different kind of imprint. One that didn’t fade.

So yes, I visited Einstein’s home. But in a way, I had already been there, decades earlier, in the mind of a child, traveling through pages without leaving the house.

Image: Photos captured by the author.