There is a unique feeling that washes over a person standing before a brutalist building. It is not the lightness of intricate design nor the soft invitation of decorative facades. Rather, it is a certain gravity, a confrontation with raw material, space, and intention.

When I recently came across an article on brutalist architecture in Metro Manila, it was more than a casual interest. It opened a door to layered memories and deeper realizations about how architecture, history, and culture intertwine. It even carried me further back — to childhood days spent in Kyoto, where I played near the bold, geometric forms of the Kyoto International Conference Center (ICC).

The brutalist landmarks in Metro Manila, such as the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) by Leandro Locsin and the MERALCO (Manila Electric Company) Building by José María Zaragoza, are more than products of their time. They are living witnesses of a nation’s aspirations, struggles, and evolving identity. Their concrete mass, softened by the tropical light, speaks both to a global movement and to something distinctly Filipino.

Brutalism and the Spirit of Early Modernism

Brutalism did not emerge merely as an aesthetic choice; it was the physical expression of a deeper hope. In the mid-twentieth century, many architects still believed that bold, geometric forms could guide humanity toward a rational, orderly future. The influence of the Bauhaus movement lingered, with its faith in minimalism, industrial materials, and the marriage of beauty and function.

In this spirit, brutalism arose as a form that was simultaneously idealistic and practical. Concrete, honest and unadorned, seemed the perfect medium for shaping a better world. The heavy volumes and sweeping lines spoke of a collective ambition, a desire to build not only structures but societies around clarity, strength, and shared progress.

From today’s perspective, these dreams often carry a bittersweet flavor. Brutalist buildings, once futuristic, now seem like artifacts from an alternate timeline; a retro-futurism where geometric ambition collided with the complex, often chaotic realities of the modern world. Yet this bittersweetness does not diminish their beauty; it deepens it.

A Global Movement and a Local Expression

Across continents, brutalism took root, responding to post-war needs for rapid construction and national renewal. In Europe, especially in Britain and the Soviet bloc, brutalism often emphasized defensive solidity. Towering complexes, civic centers, and public housing projects rose with a seriousness that reflected both social idealism and political anxieties.

The Philippines, emerging from colonial pasts and stepping into the new international order, adopted brutalism with a nuanced hand. Architects like Locsin and Zaragoza brought the spirit of international modernism but allowed it to breathe in the tropical air. Structures like the CCP and the MERALCO Building reinterpreted the heavy language of brutalism into forms that floated, shaded, and adapted to light and climate.

This transformation was not only architectural but cultural. Philippine brutalism was a conversation between inherited ideas and indigenous sensibility, resulting in spaces that felt at once monumental and intimate.

Memory Imprinted in Architecture

My connection to brutalism is layered with personal experience. During my graduate years in Osaka, I worked part-time at the National Museum of Ethnology. Designed by Kisho Kurokawa, the museum expressed a vision of modular flexibility within the concrete forms, a quiet rebellion against rigidity, even while embracing the materiality of brutalism.

Walking through its cavernous spaces, I often reflected on how architecture could shape emotional experience. It was not merely walls and halls; it was a choreography of human movement and thought.

This appreciation deepened over time. As my academic journey led me to field research and eventual settlement in the Philippines, I encountered new expressions of monumental architecture, each with their own history and gravity. Whether standing before the CCP or passing the solid grace of the MERALCO Building, I felt the echo of earlier days and the same strange kinship between form, memory, and cultural identity.

Childhood Encounters

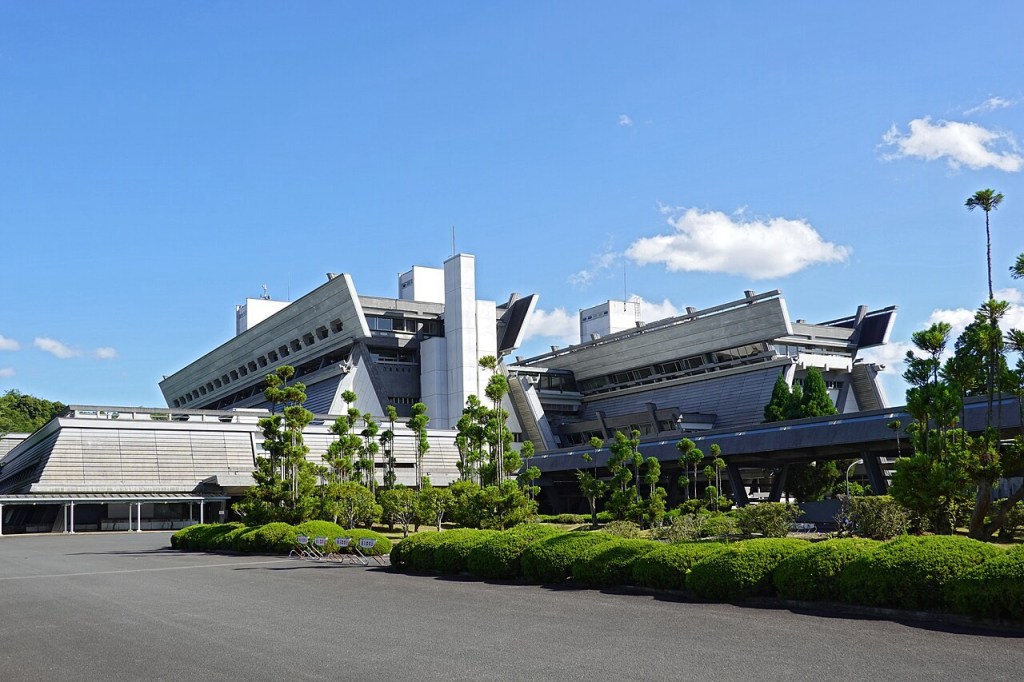

Long before my studies or conscious reflections on architecture, another memory had quietly planted itself in my heart. As a small child visiting my mother’s hometown of Kyoto, I often played near the Kyoto International Conference Center (ICC Kyoto). At that age, I had no words to categorize its design, but the feeling was unmistakable; this was not the kind of traditional beauty seen in old temples or gardens. This was something different: bold, geometric, strangely futuristic.

Only much later did I understand that ICC Kyoto, completed in 1966 and designed by Sachio Otani, belonged to the world of brutalist-modernist architecture. Its angular, modular forms, rising like a fortress and yet softened by surrounding greenery, captured the spirit of that era’s hopeful modernism.

Even as a child, without any formal knowledge, I sensed that ICC Kyoto’s aesthetics were different from the later, more fragmented designs like Tokyo Big Sight. Tokyo Big Sight, with its playful, deconstructed pyramids, belongs to a postmodern sensibility, celebrating ambiguity, play, and spectacle. In contrast, ICC Kyoto embodies a more innocent hope, a belief that bold geometry and open spaces could usher in a rational and harmonious world.

In this way, my earliest architectural memories are woven into the same conversation between brutalism, modernism, and the dreams, and disillusionments, of the twentieth century.

The Political Undertones of Monumentality

It is impossible to understand Philippine brutalism without facing its political backdrop. The Marcos regime, with its ambitious nation-building agenda, used architecture as a visual language of power and modernity. Grand structures were not merely civic facilities; they were messages, statements of vision, control, and aspiration.

The CCP Complex, the Philippine International Convention Center (PICC), the Philippine Heart Center; all were part of this strategy. Brutalism’s imposing forms carried the symbolism of endurance and authority. Yet these buildings also captured more than propaganda; they captured a complex cultural moment where artistic ambition and political theater entwined.

Today, the same structures stand as layered monuments; silent about their origins, but eloquent in their continued presence.

Brutalism’s Tropical Soul

In the Philippines, brutalism adapted itself to more than politics; it adapted to life itself. The heavy forms lifted, the interiors opened, and the exteriors shaded against the tropical sun. Spaces like the CCP allow for both grand performances and quiet strolls. The vast, shaded areas underneath Locsin’s floating volumes invite gathering, movement, and rest.

Unlike the defensive brutalism of colder climates, Philippine brutalism seems almost to invite dialogue, with air, light, water, and human presence. It reflects not just an aesthetic but a lived understanding of environment and community.

The Japanese Connection

Brutalism found fertile ground in Japan as well. Architects like Kenzo Tange bridged modernist ideals with an emerging Japanese sensibility that prized structure, rhythm, and environmental harmony. Structures like St. Mary’s Cathedral and the Yoyogi National Gymnasium stand as proof that even within concrete, one could find a language of grace.

Later, with the Metabolist movement, figures like Kisho Kurokawa pushed these ideas into new territories. Buildings became systems, capable of growth and transformation. The National Museum of Ethnology, where I once moved quietly among its concrete halls, is part of this vision—a dream not only of building for today but of adapting for tomorrow.

Both Japan and the Philippines demonstrate how brutalism could be a vessel for local spirit rather than an imported style frozen in foreign ideals.

The Passage of Time

Brutalist buildings, perhaps more than most, carry the marks of time visibly. In Europe, many fell into decay, rejected by a public that associated them with bureaucratic failure or political oppression. Weather and neglect gnawed at their surfaces, turning bold forms into crumbling relics.

In the Philippines and Japan, the story is subtler. The tropical climate weathers concrete differently, adding layers of moss, sun-bleaching, and softness. Memory, too, treats these structures differently. They are seen not only as remnants of political moments but as familiar presences; spaces where life unfolded, whether grandly or simply.

Walking past the CCP or revisiting ICC Kyoto, the sensation is similar: these are not ruins, but chapters still speaking from the unfinished book of modernity.

Reflection and Renewal

There is something quietly profound about the renewed interest in brutalism. In a world increasingly dominated by sleek, ephemeral architecture, the stubborn physicality of brutalist structures reminds us of endurance, ambition, and the human desire to shape the world meaningfully.

For me, brutalism ties together a thousand memories; studying in Osaka, walking through fields in Kyoto, attending events in Manila, and simply standing before walls that speak of dreams larger than any one generation. It is a connection to an era that dared to believe in the power of form, even when history would later complicate that belief.

Brutalism invites not only admiration but reflection.

An Invitation to See Anew

Perhaps it is time to plan a quiet pilgrimage; to visit again the spaces that once symbolized the future and now offer a different kind of presence. From the sweeping forms of the CCP to the bold angles of ICC Kyoto, there are monuments waiting not merely to be photographed but to be inhabited anew by memory and imagination.

In their silence, their gravity, and their unexpected grace, these buildings still carry the unfinished dreams of those who dared to imagine that space itself could make us better.

They are, even now, alive.

Image: Photos captured by the author and from Wikipedia