In May 2016, we gathered in front of a modest care home in Miyazaki, Japan, where elderly residents were looked after. My grandmother sat at the center, calm and radiant in her wheelchair, surrounded by three generations of family. She was 103 years old. Looking back, I now realize how important that visit was, not just for the joy of seeing her again, but for what she embodied. She was the last living witness in our family to a century of enormous change and unimaginable hardship.

She passed away not long after that photo was taken. But what remains vivid to me is not only her face in that final family picture, but the long, complex path she had walked, a path that speaks volumes about the world we live in, and the one we often forget.

We often speak about the twentieth century as a time of progress, innovation, and rising standards of living. But what my grandmother lived through tells a different story, or at least a more balanced one. It was a time of devastation and upheaval, marked by two global wars, state violence, and the suppression of voices that did not conform. Her life, and that of her father before her, were shaped not just by societal changes, but by the moral costs of history itself.

The Earthquake and the City

My grandmother left her hometown in Miyazaki and moved to Tokyo to study at Ochanomizu University, an extraordinary act in the early twentieth century when higher education for women was still a rare path. It’s not hard to imagine the courage it took for her to pursue knowledge in a male-dominated world. What she might have read, who she might have met, what ideas stirred in the classrooms of that institution. I can only guess. But one thing is certain: she was there during a time when Japan stood at the crossroads of tradition and modernity.

The Great Kanto Earthquake struck in 1923. It devastated Tokyo and the surrounding regions, destroying homes, killing over a hundred thousand people, and reshaping the lives of those who survived. Whether she was in Tokyo during the quake or arrived shortly after, the event would have left its mark on her consciousness. Natural disasters at that scale don’t just wreck infrastructure; they shake the foundations of certainty. For a young woman pursuing education far from home, it must have been a moment that clarified the fragility of human plans.

But she remained. She studied. She grew. And she returned home with knowledge that her community likely held in high regard, particularly because it came from a woman at a time when women were still expected to remain silent and unseen.

The Pastor Who Refused to Bow

Her father, my great-grandfather, was a pastor in the Holiness denomination, a branch of Protestant Christianity that emphasized spiritual renewal and individual transformation. He tried to plant seeds of faith in the soil of rural Miyazaki, building a church that still stands today. I’ve visited that church. I’ve touched its walls. It feels like something more than a building. It feels like a quiet testament to a man who believed in something larger than himself.

During World War II, religious groups in Japan were not exempt from state scrutiny. In fact, the government viewed many forms of Christianity as foreign and potentially subversive. The Holiness movement, which was independent and difficult to control, became a target. My great-grandfather was imprisoned, and like many others at the time, he was tortured by the Special Higher Police.

The fact that someone could be punished for praying in the wrong way, for refusing to align their beliefs with government propaganda, is a chilling reminder of what that era entailed. It wasn’t only about bombs and tanks. It was about the silencing of dissent, even in the quietest corners of faith. He suffered for his beliefs. And yet, the church remained. That, too, says something profound.

Human Rights Before the Idea Took Root

We talk today about human rights as if they’ve always existed. But for my grandmother’s generation, there was no safety net of international law, no presumption that one’s dignity was protected. The idea that a citizen could question the government, or follow a religious path outside state control, was not part of the societal vocabulary. The moral infrastructure we now take for granted was only beginning to form.

She lived through the Second World War, its scarcities, and its consequences. She saw the imperial dreams of her country unravel, the devastation of firebombs, the reckoning of defeat. What must it have been like to hear the Emperor’s voice on the radio, surrendering for the first time in history? What must it have been like to survive and start again?

I imagine her as a young woman during the war, perhaps with ration tickets in hand, walking through streets still bearing scars from air raids. Perhaps she was already a mother by then, worrying about the future while trying to make do with whatever she could gather. And yet, like so many of her generation, she did not dwell on the trauma. She rebuilt. Quietly. With persistence. Without complaint.

A Century of Contradictions

If the pre-modern era was defined by hardship and survival, the twentieth century promised something different, something better. Science advanced. Medicine extended lives. Literacy spread. For many, life became longer, healthier, and more connected. And yet, the contradictions of the century run deep. With progress came destruction. With invention came new means of violence. And with unity came authoritarian demands for conformity.

My grandmother’s life was not only shaped by historical events but also by the complicated forces at play beneath them. Industrialization brought electricity, trains, and communication, but also created factories that fed the war machine. Nationalism promised pride and belonging, but morphed into militarism that suppressed thought and demanded sacrifice. Even education, a gift she was privileged to receive, did not spare her from the consequences of living in a society at war with itself.

This is the world she navigated. It was not black and white. There was no clear path forward. People survived not because they understood the world, but because they adapted to it, day by day, moment by moment. They lived through what philosophers call the “disenchantment of the world” when old beliefs lost their power, and new ideologies fought for control over hearts and minds.

What amazes me most is how little she talked about it. Like many from her generation, she did not burden others with stories of suffering. But the weight was there, in the quiet pauses, the firm gaze, the way she carried herself. That was how they lived: not by forgetting the past, but by folding it neatly into silence.

The Illusion of Unbroken Progress

We often think of history as a steady climb toward something better. But progress is not a ladder, it’s a winding path, full of detours and dead ends. The twentieth century looked like a triumph from afar. But up close, in the lives of ordinary people like my grandmother, it was much more complicated.

She saw Japan modernize at a breathtaking pace. She witnessed the post-war economic miracle, the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, the rise of consumer culture, and the dawn of the digital age. Her world transformed, from handwritten letters to mobile phones, from wooden houses to concrete towers, from rice paddies to bullet trains.

But with every step forward, something was also left behind. Villages emptied. Family structures shifted. The intimacy of communities gave way to anonymous urban life. The values that once held people together were gradually replaced by the pursuit of productivity and convenience. Beneath the surface of prosperity, there was quiet loss.

She never complained. She adapted. But I often wonder what she thought about the pace of it all. Whether she ever missed the old rhythms, the slowness of conversation, the comfort of traditions, the texture of a life not yet flattened by screens and schedules. Perhaps she found comfort in the faith her father had passed on. Perhaps that’s what helped her stay rooted, even when the world around her changed beyond recognition.

Memory as Resistance

Remembering is not just an act of nostalgia. It is a form of resistance. In a world obsessed with speed, with forgetting, with moving on, to remember is to say: this mattered. She mattered. The life she lived, quiet, faithful, enduring, is not less important just because it didn’t make headlines.

Her generation rarely wrote memoirs or posted photos online. Their legacy wasn’t stored in digital clouds but in real human connections. In the stories passed down during dinners. In the family gatherings around her wheelchair. In the church built by her father, still standing in Miyazaki like a stone witness to hope.

When I look at that family photo, I don’t just see a moment frozen in time. I see a bridge. Between a century of fire and a future still unknown. Between a woman who lived through it all and the descendants who owe their lives to her strength. She did not ask to be remembered. But she deserves to be.

And remembering her is also a way of remembering everything her life touched: the women who studied when few were allowed to; the pastors who kept their faith in times of oppression; the families who rebuilt after the bombs fell; the ordinary people who refused to surrender their dignity, even when no one was watching.

What They Handed Down

What did she pass on to us, beyond the blood in our veins?

Perhaps it’s the value of endurance. Not the flashy kind that wins medals, but the quiet kind that wakes up each day and does what must be done. Perhaps it’s the importance of standing firm in what you believe, even when the world says no. Perhaps it’s the humility of knowing that you don’t need to be seen to make a difference.

We live now in an age of rights, voices, and choices. And yet, we often lack the strength that came so naturally to her generation. We forget that freedom was not given. It was often bought at a great cost. We forget that the world we enjoy today was shaped not only by heroes, but by people like her, who lived full and faithful lives without asking for recognition.

There is something deeply grounding about that. Something deeply human. In an age that often feels chaotic and fragmented, remembering people like my grandmother reminds us that continuity still exists. That values can be passed down. That faith, once planted, can grow even across generations.

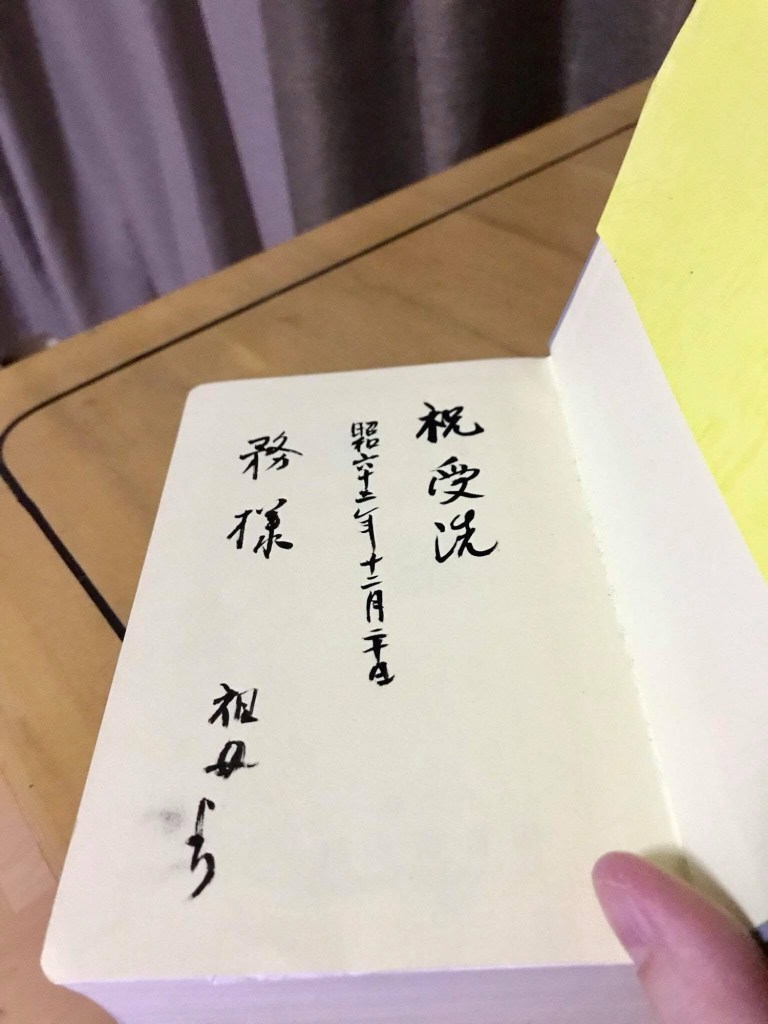

I still keep with me the Japanese Bible she gave me during my baptismal confirmation, a precious moment in my life. On the opening page, she wrote a message in her own brush calligraphy to celebrate that day. It wasn’t just a note; it was a gesture from a woman who had carried her faith through war, loss, and age, and now passed it to me, her grandson. I can feel the weight of that spiritual inheritance every time I open it. The book is old now, but her words remain alive, steady, graceful, just like she was.

The Sacred Work of Remembering

We tend to think of history as something found in museums or textbooks. But some of the most important histories live quietly—in family homes, in aging photos, in the fading memories of those who came before us. To remember them is not only an act of gratitude. It is a sacred responsibility.

My grandmother lived through wars, earthquakes, persecution, economic rebirth, and cultural upheaval. She lived through a century that bent the world out of shape. And yet, she remained intact. Not untouched, but unbroken. And in doing so, she gave the rest of us a foundation to stand on.

The twentieth century was not only about global events. It was about people like her, who held the world together in their own small, persistent ways. Who made meals. Who raised children. Who kept the faith when it would have been easier to let it go. Who didn’t write history books, but lived the kind of history that truly matters.

We remember her not just because she was our grandmother. We remember her because her life shows us what it means to be human when the world forgets.

Image: Photos captured by the author.

Nice post 🙏🎸

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! 😊

LikeLike