The Japanese language, like all languages, began as a purely oral tradition. The transformation into written form came through the adoption of Chinese characters, marking the beginning of Japan’s complex relationship with written communication. These borrowed characters, known as Manyōgana, served as the foundation for recording Japan’s earliest literary works, including “Kojiki” and “Manyōshū.”

As Japanese society developed, particularly during the Heian period (794 to 1185), two new writing systems emerged from the simplified forms of Chinese characters. Female aristocrats created Hiragana, which became the script of choice for literary works like “The Tale of Genji.” Simultaneously, the Buddhist monk Kūkai developed Katakana, originally used for religious texts and scholarly annotations.

This tripartite writing system—Kanji, Hiragana, and Katakana—became the standard for Japanese written communication, though it presented unique challenges for modernization in later centuries.

The Japanese writing system’s evolution exemplifies a pattern in the development of writing systems worldwide. When societies encounter foreign writing systems, they rarely adopt them wholesale; instead, they adapt and transform them to suit their linguistic needs. This process of adaptation, seen in how Japan modified Chinese characters to create Hiragana and Katakana, shows how writing systems evolve through cultural exchange and creative innovation rather than mere imitation.

Early Modernization and the Typewriter Challenge

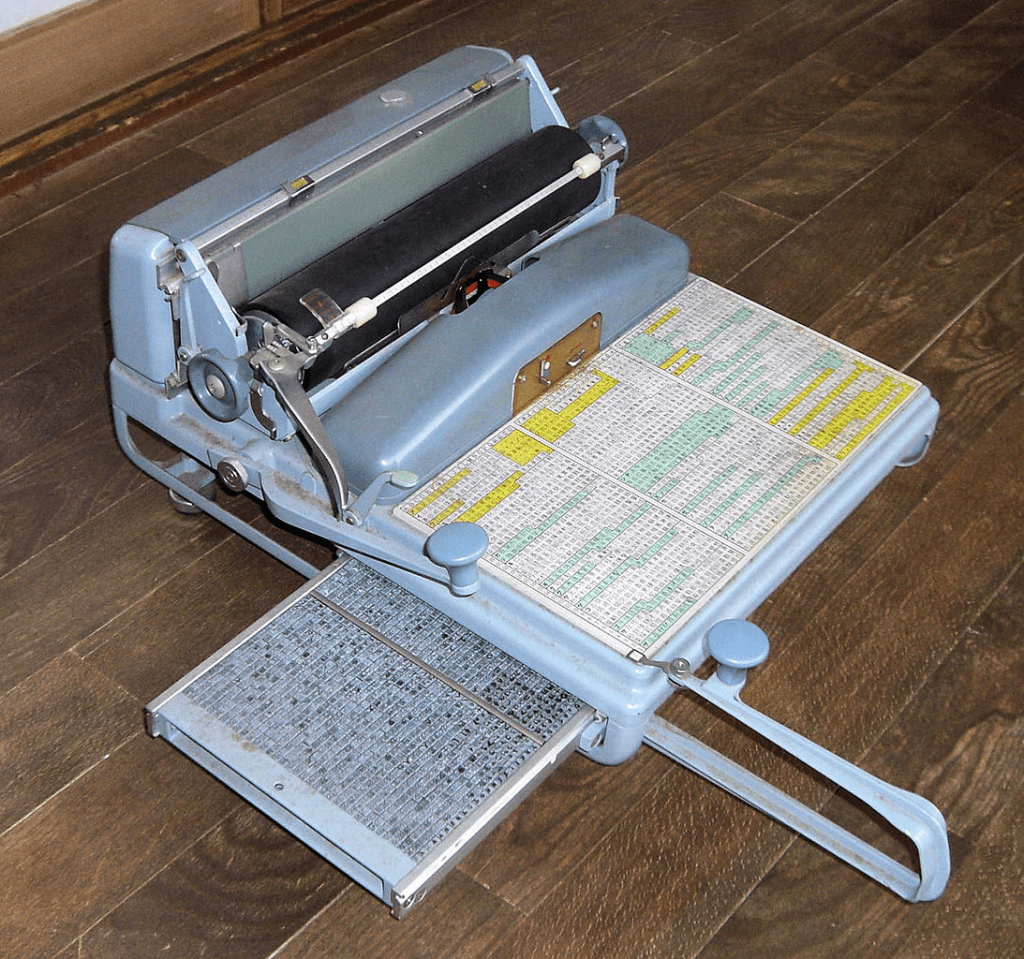

The dawn of the twentieth century brought new technological demands that tested Japan’s complex writing system. The invention of the typewriter, revolutionary for alphabetic languages, posed a particular challenge for Japanese with its thousands of characters.

Japanese inventors responded with several innovative solutions. One approach involved a large board containing thousands of characters, where operators would manually select each character—more akin to typesetting than typing. Another solution utilized only Hiragana or Katakana, limiting the character set to around fifty symbols but sacrificing the nuance and readability that Kanji provided.

The third option—using romanized Japanese (rōmaji)—seemed promising from a technological standpoint but faced resistance from native readers who found it difficult to comprehend text without the visual cues provided by the traditional character mix.

The Romanization Movement

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of the romanization movement, led by remarkable individuals who recognized the need to modernize Japanese writing. Aikitsu Tanakadate, a physicist by training, developed the Nihon-shiki romanization system and demonstrated his commitment by using romaji in his personal and professional life.

Takuro Tamaru, another scientist-turned-language reformer, made substantial contributions through his work “Rōmaji Kokujiron” and his efforts to establish proper word separation in romanized Japanese. His background in physics at Tokyo Imperial University and studies in Germany gave him a unique perspective on the importance of modernizing Japanese writing for international communication.

The movement gained additional depth through figures like Takuboku Ishikawa, whose “Romaji Diary” demonstrated a practical, if personal, use of romanization. Later, Tadao Umesao’s leadership of the Japan Romaji Society into the modern era showed the movement’s enduring relevance, particularly as he advocated for reform after losing his vision.

The Digital Revolution

The revolutionary breakthrough in Japanese writing technology came through Ken-ichi Mori’s pioneering work in the early 1970s. As the lead developer of the first Japanese word processor, Mori laid the groundwork for what would become the standard method of Japanese text input. His innovations culminated in Toshiba’s release of the JW-10 in 1978, which introduced practical kana-to-kanji conversion technology.

The system’s success was remarkable, with production reaching 2.71 million units annually by 1989. The cumulative sales exceeded 30 million units by 2000, demonstrating the profound impact of this technology on Japanese communication.

The genius of this system lies in its intuitive input method. Users type Roman letters (romaji) which automatically convert to hiragana on screen. For example, typing “a” produces “あ” and “ka” produces “か”. Once the desired word is typed in hiragana, pressing the spacebar presents a dropdown menu of kanji conversion options. Users can then select the appropriate kanji based on context and meaning.

This conversion system was particularly sophisticated for its time. The JW-10’s dictionary contained 54,000 ordinary words and 8,000 proper nouns as standard, with the capacity to store an additional 18,000 user-defined words. The system could handle complex conversions by considering sentence context and frequency of use, effectively addressing the challenge of Japanese homophones—words that sound identical but are written with different kanji.

A Visionary Beyond Anthropology

Tadao Umesao (1920-2010) was more than just a supporter of writing reform. As a renowned anthropologist and intellectual, he predicted the emergence of the information society decades before its arrival. His 1963 work “Information Industry Theory: Dawn of the Coming Era of the Ectodermal Industry” accurately foresaw today’s advanced information society.

His contributions extended far beyond academia. As the founding director-general of the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, he revolutionized museum practices. His numerous publications, including “The Art of Intellectual Production” (1969), proposed information organization methods that paralleled modern computer systems.

Umesao’s work spanned multiple disciplines and cultures. His books, including “Civilization Theory on Information” (1988) and “Women and Civilization” (1988), demonstrated his broad intellectual reach. His insights into Japanese civilization earned him numerous accolades, including the Order of Culture and the status of Person of Cultural Merit in both Japan and Mongolia.

Legacy and Modern Impact

The story of Japanese writing modernization reveals how technological constraints can lead to unexpected solutions. While the romanization movement never achieved its goal of replacing traditional Japanese writing, its influence can be seen in the modern Japanese typing system, where users effectively type in romaji even if they never see it on screen.

The dissolution of the Japan Romaji Society in 2023 marked the end of an era, but the principles its members fought for—efficiency, accessibility, and modernization—live on in current technology. Today’s Japanese computer users unconsciously fulfill part of the romanization advocates’ vision every time they type, even as they read and write in traditional characters.

This synthesis of traditional writing and modern input methods demonstrates how cultural preservation and technological progress need not be mutually exclusive. The Japanese writing system’s evolution from borrowed Chinese characters to modern digital input methods shows how innovation can honor tradition while meeting contemporary needs.

Looking Forward

As technology continues to advance, new challenges and opportunities in Japanese writing will surely emerge. Voice recognition, artificial intelligence, and other innovations may further transform how Japanese is written and processed. However, the lessons learned from the past century of adaptation suggest that future solutions will likely continue to balance preservation of traditional writing with the demands of modern communication.

The history of Japanese writing modernization teaches us that the most successful solutions often come not from replacing traditional systems entirely, but from finding innovative ways to adapt them to new requirements. This principle continues to guide the development of writing technologies not just in Japan, but across all languages with complex writing systems.

The Japanese case offers valuable insights into the relationship between technology and writing systems globally. It demonstrates that successful technological solutions emerge not from forcing writing systems to conform to technology, but from developing technology that respects and enhances existing linguistic and cultural practices. This lesson remains crucial as we face new challenges in digital communication and artificial intelligence across all languages and writing systems.

Image: Japanese typewriter