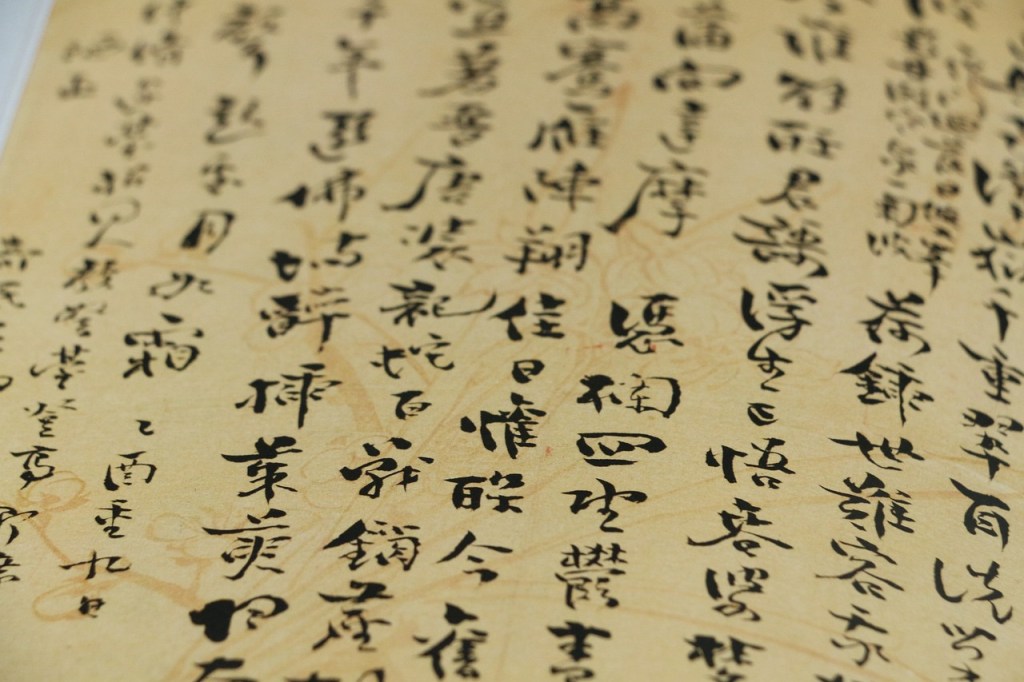

The relationship between Chinese characters and East Asian societies presents a compelling study in contrasts. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as Western influence swept across Asia, these ancient writing systems faced unprecedented scrutiny. The colonial era brought stark awareness of Western technological and economic advantages, leading many to question whether the intricate system of Chinese characters hindered progress, particularly in education.

The practical challenges were clear: while alphabetic systems required mastering only about thirty letters, East Asian students invested years in learning thousands of characters. This disparity became especially apparent as typewriters and early computers transformed office work and communication. The binary choice seemed stark: maintain cultural heritage or embrace technological efficiency.

This tension sparked varied responses across East Asia. Korea developed Hangul and largely moved away from Chinese characters, while Vietnam adopted a Roman alphabet system. Japan maintained a hybrid approach, preserving kanji while integrating it with phonetic scripts, despite significant pressure to romanize, including from post-World War II American administrators. Even China, the origin of these characters, seriously debated their continued use, ultimately choosing to simplify rather than abandon them.

The English Language Phenomenon

The global dominance of English presents a parallel to the persistence of Chinese characters. Despite its notorious irregularities in spelling, pronunciation, and idioms, English has become the international language of business, technology, and cultural exchange. This dominance persists even though English is not particularly easy to master, as evidenced by the thriving industry of “speak like a native” training and countless resources dedicated to mastering its nuances.

The comparison with Esperanto is particularly revealing. Esperanto, designed for maximum rationality and ease of learning, would seem the perfect choice for international communication. Yet it remains a niche language while English, with all its complexities, continues to expand its influence. This suggests that language adoption follows paths determined more by political, economic, and cultural power than by inherent efficiency or ease of use.

The role of English in programming and artificial intelligence further cements its position, even as these technologies increasingly accommodate other languages. This technological entrenchment mirrors how Chinese characters, despite their complexity, have found new life in the digital age through sophisticated input methods and processing capabilities.

Historical Precedents

The pattern of complex languages achieving widespread influence has historical precedents. Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin each served as vehicles of civilization in their respective spheres, carrying not just communication but entire worldviews and ways of thinking. French later assumed a similar role in European diplomacy and culture. None of these languages were particularly simple or easy to learn, yet each maintained its position through cultural and political power rather than linguistic efficiency.

These historical examples suggest that language dominance often correlates with civilization’s centers of gravity. Sanskrit spread with Indian philosophical and religious thought, Greek with Hellenistic culture, Latin with Roman law and Catholic Christianity, and French with European enlightenment and diplomacy. Each language, despite or perhaps because of its complexity, became a repository of sophisticated thought and cultural expression.

The persistence of these languages, even after their associated empires declined, demonstrates how linguistic influence can outlast political power. Latin remained the language of scholarship well into the modern era, while Classical Chinese continued to influence East Asian intellectual life long after China’s political dominance waned. This suggests that complex languages, once established as carriers of civilization, develop a cultural momentum that transcends their original practical purposes.

Future Prospects in a Digital Age

The digital revolution initially appeared to favor simpler writing systems, as early computers struggled with character-based languages. However, technological advancement has largely overcome these limitations. Modern computing power, sophisticated input methods, and improved character recognition have eliminated many practical barriers to using complex writing systems.

Yet questions about the future of language dominance remain relevant. Will English maintain its global position as technology evolves? Might Chinese expand its influence alongside China’s economic rise? Could new technologies fundamentally alter how languages compete and evolve? The historical pattern suggests that the next dominant language, if there is one, might not be the most logical or efficient choice.

The unprecedented interconnectedness of the modern world adds new dimensions to these questions. Translation technology, global communication networks, and artificial intelligence are changing how languages interact and evolve. These developments might either reinforce existing language hierarchies or create new patterns of linguistic influence that break with historical precedent.

A Path Forward

The persistence of complex languages like Chinese characters and English challenges purely rational approaches to language and communication. Their continued dominance, despite the availability of simpler alternatives, suggests that languages serve purposes far beyond mere information transfer. They carry cultural heritage, enable sophisticated expression, and maintain connections across generations.

This understanding helps explain why attempts to replace these systems with more “rational” alternatives often fail. The value of a language system lies not just in its efficiency but in its ability to carry cultural meaning and facilitate complex thought. As technology continues to evolve, it may be that the most successful languages will be those that balance preservation of these deeper cultural functions with adaptation to new forms of communication.

The future may not require choosing between tradition and progress. Instead, as demonstrated by the successful digitization of Chinese characters and the global spread of English despite its complexities, we might find ways to maintain rich linguistic traditions while embracing technological advancement. This synthesis could preserve the cultural depth of complex languages while enhancing their practical utility in an increasingly digital world.

Image by quillau