A soft coo, a babble, then suddenly—words. The journey from helpless infant to eloquent speaker is one of life’s most remarkable transformations, yet it unfolds with such regularity that we often take it for granted. But how exactly does this miracle of language acquisition occur? This question has puzzled philosophers, linguists, and scientists for centuries, spawning theories as diverse and complex as language itself.

Imagine, for a moment, the mind of a child as a vast, uncharted territory. In this landscape, three distinct pathways have been proposed, each offering a unique route to linguistic mastery:

First, we encounter the grand architecture of Noam Chomsky’s Universal Grammar—a theory that posits an innate, biological blueprint for language within every human brain. This path suggests that we are born with the basic structures of language already in place, needing only the spark of experience to bring them to life.

The second path is well-trodden and carefully maintained—the road of Prescriptive Grammar. Here, language is a set of rules to be learned and followed, a code of communication passed down through generations and codified by linguistic authorities. This is the path of “proper” speech, of style guides and grammar books.

Our third path is the newest and perhaps the most controversial—the data-driven highway of Artificial Intelligence. This route suggests that language can be mastered through sheer exposure and pattern recognition, without the need for innate structures or explicit rules. It’s a path that has produced remarkable results, yet also raised profound questions about the nature of language and cognition.

On this exploration of language acquisition theories, let’s explore our own linguistic journey. How did we come to master the intricacies of our mother tongue? And as we dive into each perspective, we’ll uncover not just theories of language, but reflections on human nature, the workings of the mind, and the very essence of what it means to communicate.

Chomsky’s Tower: The Edifice of Innate Grammar

Picture, if you will, a towering structure rising from the misty foundations of the human mind. This is Chomsky’s Tower—a theoretical edifice built on the revolutionary idea of Universal Grammar. At its core lies a provocative claim: that the capacity for language is not merely learned, but innate to the human species.

Noam Chomsky, the architect of this theory, proposes that all human beings are born with a “language acquisition device”—a neural framework that comes pre-loaded with the fundamental principles of language. This universal grammar, Chomsky argues, is the skeleton key that unlocks the ability to learn any human language.

Consider a young child effortlessly mastering the complexities of their native tongue—a feat that would challenge even the most sophisticated computer programs. How does this miracle occur? Chomsky’s answer lies in what he terms “the poverty of the stimulus.”

Imagine trying to learn a language by only hearing fragmented, often ungrammatical snippets of conversation. This, Chomsky points out, is precisely the linguistic environment most children inhabit. Yet, despite this impoverished input, children consistently acquire language with remarkable speed and accuracy. This observation led Chomsky to a startling conclusion: the input children receive is simply insufficient to account for the complexity and universality of their linguistic output. There must, he reasoned, be some innate structure guiding this process—a kind of linguistic DNA encoded in our genes.

The implications of Chomsky’s theory stretch far beyond the realm of linguistics. If language is indeed innate, it suggests a deep biological basis for human communication. The universality of grammar implies a fundamental unity in human cognition, transcending cultural and linguistic boundaries. In this light, language acquisition becomes less a process of learning from scratch, and more one of activating latent knowledge—as if we’re all born with a dormant linguistic ability, waiting to be awakened by the sounds of our mother tongue.

Yet, Chomsky’s Tower is not without its critics. Some linguists and cognitive scientists argue that it underestimates the role of environmental factors in language development. They point to the incredible diversity of world languages as evidence against a universal grammar. After all, if we all share the same innate linguistic structures, why are there so many different ways to express even the simplest ideas across languages?

Despite these challenges, Chomsky’s ideas continue to cast a long shadow over the field of linguistics. They invite us to reconsider not just how we learn language, but what it means to be human in a world shaped by words. His theory suggests that language is not just a tool we pick up along the way, but a fundamental part of our biological inheritance—as innate to us as our ability to walk upright or use tools.

As we scale the heights of Chomsky’s Tower, we’re left with a vertiginous view of language as something both deeply personal and universally shared—a bridge between the individual mind and our collective human heritage. It challenges us to see every conversation, every written word, as not just an act of communication, but as an expression of our shared humanity, encoded in the very structure of our brains.

Wether one fully embraces Chomsky’s theory or not, its impact on our understanding of language is undeniable. It has shifted the conversation from seeing language as a purely learned skill to viewing it as a fundamental aspect of what makes us human. As we continue our journey through the landscape of linguistic theories, Chomsky’s Tower stands as a monument to the idea that perhaps, in the deepest recesses of our minds, we all speak the same language.

The Grammarian’s Grip: Prescriptive Rules and Social Norms

As we descend from the lofty heights of Chomsky’s Tower, we find ourselves on a well-trodden path, paved with the stones of tradition and lined with signposts of correctness. This is the domain of Prescriptive Grammar, where language is not so much a natural phenomenon as it is a carefully cultivated garden.

Imagine a stern-faced grammarian, red pen in hand, ready to strike through any errant comma or dangling participle. This figure, both revered and feared, represents the guardians of “proper” language use. Their mission? To maintain the purity and precision of language against the erosive forces of colloquialism and change.

The roots of prescriptive grammar run deep, stretching back to the first attempts to codify language rules. In the hallowed halls of language academies and the pages of style guides, these arbiters of correctness have long held sway over how we should speak and write. Their influence extends from the classrooms where children learn to diagram sentences to the boardrooms where the “right” way of speaking can make or break careers.

But what gives these rules their power? The answer lies not in any innate linguistic truth, but in social convention and cultural authority. Prescriptive grammar is, in essence, a set of agreed-upon norms that signal education, class, and belonging. To speak “correctly” is to demonstrate one’s membership in a particular social group, to show that one has mastered the intricate dance of linguistic etiquette.

This approach to language has undeniable benefits. Standardization allows for clear communication across vast distances and diverse populations. It provides a common ground for legal documents, scientific papers, and international diplomacy. In a world of linguistic chaos, prescriptive grammar offers an anchor of consistency.

Yet, this rigid adherence to rules comes at a cost. The prescriptivist view often fails to account for the natural evolution of language, treating change as degradation rather than adaptation. It can stigmatize dialects and vernaculars, creating linguistic hierarchies that mirror and reinforce social inequalities. The insistence on “correct” usage can stifle creativity and self-expression, turning the richness of language into a monochromatic canvas.

Moreover, the prescriptive approach sometimes clashes with the realities of how language is actually used. Split infinitives, sentence-ending prepositions, and other so-called errors have been part of natural speech for centuries, used by even the most celebrated writers. The gap between prescribed rules and actual usage raises a profound question: Who truly owns language – the grammarians or the speakers?

As we navigate this realm of rules and regulations, we’re forced to confront the tension between tradition and innovation, between uniformity and diversity. The Grammarian’s Grip reminds us that language is not just a means of communication, but a mirror of social values and power structures.

Prescriptive grammar serves as both a tool and a challenge. It offers a framework for clear communication while simultaneously inviting us to question the nature of linguistic authority. As we continue our journey through the landscape of language theories, we carry with us the weight of these rules – and the freedom to decide when to follow them, and when to forge our own linguistic paths.

The AI Alchemist: Turning Data into Discourse

As we venture further into the landscape of linguistic theory, we encounter a sight that would have been unimaginable just a few decades ago: vast digital laboratories where language is distilled not from rules or innate structures, but from raw data. Welcome to the domain of the AI Alchemist, where the base metal of countless texts is transmuted into the gold of fluent discourse.

Picture a tireless digital entity, consuming millions of books, articles, and conversations, extracting patterns and probabilities with inhuman precision. This is the essence of large language models, the cutting edge of artificial intelligence’s approach to language. Unlike Chomsky’s innate structures or the prescriptivist’s rigid rules, these models learn language through sheer exposure and statistical analysis.

The process is both simple and mind-bogglingly complex. At its core, it’s about prediction: given a sequence of words, what’s most likely to come next? By training on vast corpora of text, these models develop an uncanny ability to generate coherent and contextually appropriate language. It’s as if they’ve internalized the patterns of human communication, learning to mimic our linguistic behavior with startling accuracy.

The results can be astonishing. AI language models can engage in conversations, answer questions, and even create original content across a wide range of topics and styles. They can translate between languages, summarize complex texts, and even attempt creative writing. All this, without any explicit knowledge of grammar rules or linguistic theory.

This approach has sent shockwaves through the world of linguistics and cognitive science. It challenges long-held assumptions about the nature of language acquisition and processing. If a machine can produce human-like language simply by analyzing patterns, do we need to posit innate grammatical structures? If fluent communication can emerge from statistical learning, what does this say about the nature of human language faculty?

Yet, for all their impressive capabilities, these AI alchemists have their limitations. They can produce text that is grammatically correct and contextually appropriate, but do they truly understand the meaning behind the words? They can mimic human language use, but can they engage in genuine reasoning or possess true creativity? These questions touch on deep issues in philosophy of mind and the nature of intelligence.

Moreover, the AI approach to language is not without its ethical concerns. These models, trained on human-generated text, can inadvertently perpetuate biases present in their training data. They raise questions about authorship, originality, and the future of human-generated content in a world where machines can produce human-like text at scale.

As we observe the AI Alchemist at work, we’re forced to reconsider our understanding of language itself. Is language fundamentally a set of rules to be followed, a biological endowment to be awakened, or a statistical pattern to be learned? The success of AI in generating fluent language suggests that perhaps it’s a bit of all three – and maybe something more that we’ve yet to fully grasp.

The AI approach to language offers both a powerful tool and a profound challenge to our understanding of human communication. As we continue our journey through the linguistic landscape, we carry with us the questions it raises: about the nature of meaning, the essence of understanding, and the future of human-machine interaction in the realm of language.

The Crossroads: Where Theories Converge and Diverge

As we pause at this linguistic crossroads, we find ourselves at a unique vantage point. Behind us lie the paths we’ve traveled: Chomsky’s towering edifice of innate grammar, the well-trodden road of prescriptive rules, and the data-driven highway of AI language models. Each offers a distinct perspective on the nature of language, its acquisition, and its use. But here, at this intersection, we begin to see how these seemingly disparate views intertwine, clash, and ultimately enrich our understanding of human communication.

Let’s first consider the points of convergence. All three approaches acknowledge the remarkable complexity of language and the astounding facility with which humans acquire it. Whether through innate structures, learned rules, or statistical patterns, each theory grapples with the fundamental question: How do we transform thoughts into words, and words into meaning?

Chomsky’s Universal Grammar and the AI’s statistical approach both seek to explain the rapidity and universality of language acquisition. While they propose radically different mechanisms, both recognize that children around the world master their native tongues with a speed and proficiency that defies simple explanation. The prescriptive grammarian, too, acknowledges this innate ability, even as they seek to shape and refine it.

Moreover, all three perspectives implicitly recognize the systematic nature of language. Whether encoded in our genes, codified in rulebooks, or extracted from vast corpora of text, language follows patterns. These patterns allow for infinite creativity within a finite system – a paradox that lies at the heart of human communication.

Yet, the differences between these approaches are as illuminating as their similarities. The nature-nurture debate takes center stage as we compare Chomsky’s biological determinism with the AI’s tabula rasa. Is language primarily an innate capacity, or is it largely learned from our environment? The success of large language models in generating coherent text challenges the notion of an innate Universal Grammar, while the poverty of the stimulus argument questions whether statistical learning alone can account for human linguistic competence.

The prescriptive approach, meanwhile, introduces a social dimension largely absent from the other two theories. It reminds us that language is not just a cognitive or computational phenomenon, but a social one. The rules of “proper” usage reflect and reinforce social hierarchies, raising questions about the relationship between language, power, and identity.

These divergences prompt us to consider deeper questions about the nature of language and cognition. What is the relationship between language and thought? Can true understanding emerge from statistical patterns, or does it require innate conceptual structures? How do social and cultural factors shape not just how we use language, but how we perceive and categorize the world around us?

The phenomenon of bilingualism and multilingualism offers a particularly rich area for exploration at this crossroads. How do multiple languages coexist in a single mind? Chomsky’s theory might suggest separate but interconnected language acquisition devices, while the AI approach might view it as simply a more complex set of statistical patterns. The prescriptivist, in turn, might focus on the societal implications of code-switching and language mixing.

As we stand at this intersection, we realize that each path offers valuable insights, but none provides a complete map of the linguistic territory. Perhaps the true power lies not in choosing one road over the others, but in synthesizing their perspectives. By combining the biological insights of Chomsky, the social awareness of prescriptivism, and the data-driven approach of AI, we may yet develop a more comprehensive understanding of language.

This crossroads reminds us that language, like the human mind itself, is too vast and complex to be fully captured by any single theory. As we prepare to continue our journey, we carry with us a richer, more nuanced view of human communication – one that embraces both the universal and the particular, the innate and the learned, the rule-bound and the statistically emergent.

Beyond the Horizon: Future Directions in Language Study

As we leave the crossroads behind and venture into uncharted territory, we find ourselves gazing towards a horizon rich with possibility. The landscape of language study is evolving rapidly, shaped by new technologies, interdisciplinary collaborations, and shifting paradigms. What lies beyond this horizon? Let’s explore some of the exciting directions that promise to reshape our understanding of language in the years to come.

Imagine a future where the boundaries between disciplines blur and dissolve. Linguists, neuroscientists, computer scientists, and anthropologists work in concert, each bringing their unique perspectives to bear on the mystery of language. This interdisciplinary approach is already bearing fruit, and its potential seems boundless.

One of the most promising frontiers is the intersection of linguistics and neuroscience. Advanced brain imaging techniques are allowing us to observe language processing in real-time, offering unprecedented insights into how the brain constructs and comprehends meaning. These studies may finally bridge the gap between Chomsky’s abstract linguistic structures and the physical architecture of the brain.

Picture a laboratory where a participant reads a sentence while lying in an fMRI scanner. As they process each word, different regions of their brain light up in a complex dance of neural activity. By mapping these patterns across many individuals and languages, researchers are beginning to decode the neural basis of language. This work could revolutionize our understanding of language acquisition, multilingualism, and even disorders like aphasia.

Meanwhile, the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence continues to challenge and inform linguistic theory. As language models become more sophisticated, they’re not just mimicking human language use – they’re providing new tools for studying it. Imagine AI systems that can simulate centuries of language evolution in minutes, allowing linguists to test theories about historical language change that were previously impossible to verify.

These AI models are also pushing us to refine our definitions of language comprehension and production. As machines become increasingly adept at generating human-like text, we’re forced to grapple with deep questions about the nature of understanding, creativity, and even consciousness. The line between human and machine language use is blurring, prompting both excitement and concern about the future of communication.

In the realm of education, these advances promise to transform how we teach and learn languages. Envision a classroom where students interact with AI language tutors tailored to their individual learning styles, or where virtual reality allows for immersive language experiences without leaving the room. These technologies could democratize language learning, making multilingualism more accessible than ever before.

Yet, as we embrace these new frontiers, we must also confront the ethical challenges they present. How do we ensure that AI language models don’t perpetuate or exacerbate societal biases? What are the implications of machines that can generate human-like text for concepts like authorship and intellectual property? As language technology becomes more powerful, questions of privacy, consent, and the potential for misuse become increasingly urgent.

Moreover, as our understanding of language grows more sophisticated, we must not lose sight of its fundamental role in human culture and identity. The future of language study must balance the pursuit of universal principles with a deep appreciation for linguistic diversity. In a world where a language falls silent every two weeks, how can we use our advancing knowledge to preserve and celebrate the full spectrum of human linguistic heritage?

As we look beyond the horizon, we see a future where the study of language is more integrated, more empirical, and more consequential than ever before. It’s a future that promises not just to satisfy our intellectual curiosity, but to reshape how we communicate, learn, and understand ourselves as a species.

The path ahead is not a single, straight road, but a web of interconnected possibilities. As we continue our journey into this linguistic future, we carry with us the insights of the past, the tools of the present, and an unwavering fascination with the power of human language. What new wonders and challenges await us in this uncharted territory? Only time – and our continued exploration – will tell.

Embracing the Complexity of Language

As our journey through the linguistic landscape draws to a close, we find ourselves not at an end, but at a new beginning. We’ve traversed the lofty heights of Chomsky’s innate grammar, navigated the well-worn paths of prescriptive rules, marveled at the alchemical transformations of AI language models, and gazed beyond the horizon to the future of language study. What have we learned from this expedition, and where do we go from here?

First and foremost, our travels have revealed language to be a phenomenon of staggering complexity and beauty. Like a fractal, it reveals new intricacies at every level of examination. From the firing of neurons to the flow of conversation, from the babbling of infants to the poetry of masters, language defies simple explanation. It is at once a biological endowment, a social construct, a computational challenge, and a window into the human mind.

We’ve seen how different approaches to understanding language – be they rooted in biology, social norms, or statistical patterns – each illuminate different facets of this multifaceted phenomenon. Chomsky’s Universal Grammar reminds us of the remarkable universality of language acquisition. Prescriptive grammar highlights the social and cultural dimensions of language use. The AI approach demonstrates the power of pattern recognition and statistical learning in replicating human-like language.

Yet perhaps the most valuable lesson from our journey is not about the superiority of one theory over others, but about the importance of intellectual humility and openness. Each perspective we’ve explored has its strengths and limitations. The true power lies in their synthesis – in our ability to draw insights from diverse approaches and weave them into a richer, more nuanced understanding of language.

As we look to the future, we see a field of study that is more integrated, more empirical, and more consequential than ever before. The boundaries between disciplines are blurring, opening up new avenues for discovery. Technology is providing us with unprecedented tools to observe, analyze, and replicate language processes. These advancements promise not only to satisfy our intellectual curiosity but also to have profound implications for education, communication, and even our understanding of what it means to be human.

Yet with these exciting possibilities come weighty responsibilities. As our power to shape and manipulate language grows, so too does our obligation to use that power wisely. We must remain vigilant against the perpetuation of biases, the erosion of privacy, and the potential misuse of language technologies. We must balance our pursuit of universal principles with a deep respect for linguistic diversity and the cultural heritage it represents.

Our journey through the linguistic landscape reminds us that language is not just an object of study – it’s a fundamental part of the human experience. It’s the medium through which we express our thoughts, share our feelings, and connect with others. It’s a mirror that reflects our cognitive processes, our social structures, and our cultural values. And it’s a tool that allows us to shape our reality, to imagine new possibilities, and to cooperate on a scale unmatched in the natural world.

The story of human language is far from over. It continues to unfold with every conversation, every written word, every new speaker who joins the global chorus of human voices. As we face the challenges and opportunities of our linguistic future, let us do so with wonder, with critical thought, and with a deep appreciation for the incredible complexity and power of human language.

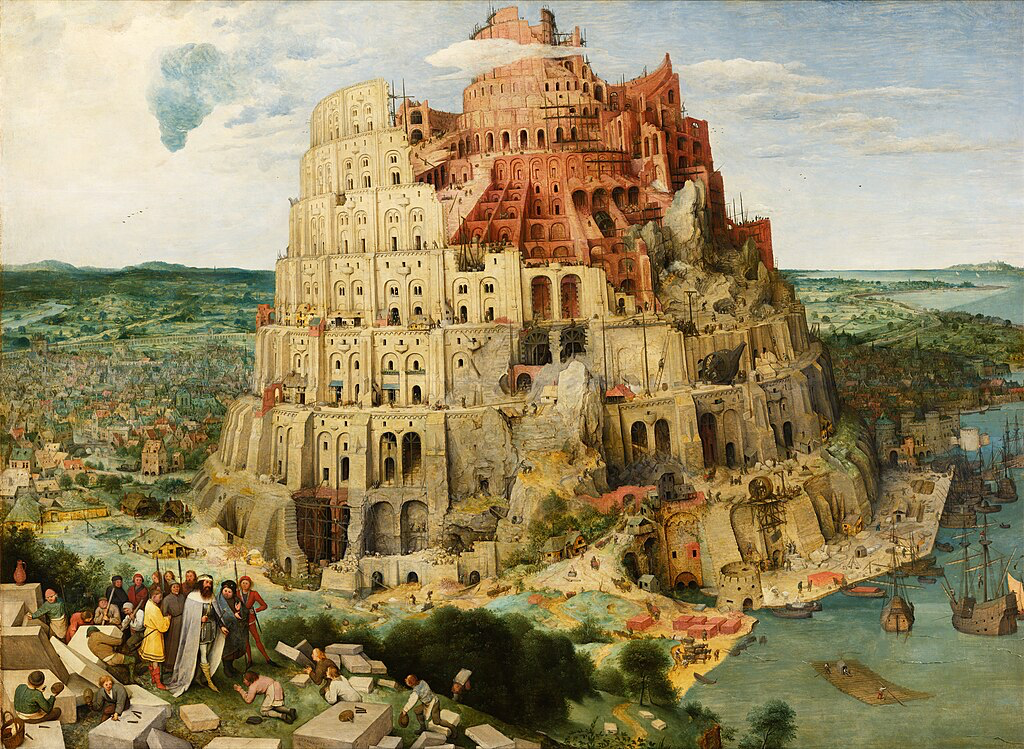

Image: The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563